#2: Combine Multiple Elements to Create an Engaging Premise

There’s a popular Studio C comedy skit called “Teddy’s Story Joint.” In it, authors go to a story restaurant and buy their plots. The first author to visit is Jane Austen, who says, “I’d like a plot today. The usual.”

A new employee asks her boss, “What’s the usual?”

He explains what Jane Austen is looking for: “Girl likes a guy. Looks like she won’t get the guy, but then she does.” He turns to Jane Austen and asks, “With the witty social critique on the side?”

Jane Austen smiles and says, “You know how I like it.”

Arguably, there might only be seven basic plots, but obviously there’s a lot more to Jane Austen than this very basic plot structure found at the core of her novels. How do you do this in your own writing: how can you make your stories different from all the other stories out there?

While almost every idea has been “done before” in some way or another, if you’re brainstorming or developing a concept it’s useful to combine multiple elements to create an engaging and original premise.

Take Jane Austen’s Persuasion as an example. Yes, it’s a love story with hiccups—but it’s so much more than that.

Here are some of the key elements that together make it a fascinating premise:

The two penguins fighting over Wentworth’s heart are Louisa and Henrietta Musgrove. Anne Elliot is the penguin on the top left, trying hard to not watch. (Penguins from the California Academy of Sciences.)

Persuasion incorporates lost love, jealousy, longing, misunderstandings, the pain of betrayal, and family conflict. It’s an engaging concept, even when written in bullet point form. The elements are distinctive and focused, they can be explained quickly and easily, and they paint a picture of the character, plot, and conflict.

How do you create an engaging premise or concept?

Take the kernel of your story idea—whether it’s a character, a plot idea, a situation, a setting—and start combining it with other things. Consider what happens if you put the story in a different time, use a different genre, or add a different subplot. What happens if you change a key detail about one of the characters? Once you start getting excited about the concept, then you know you have something worth writing.

Exercise 1:

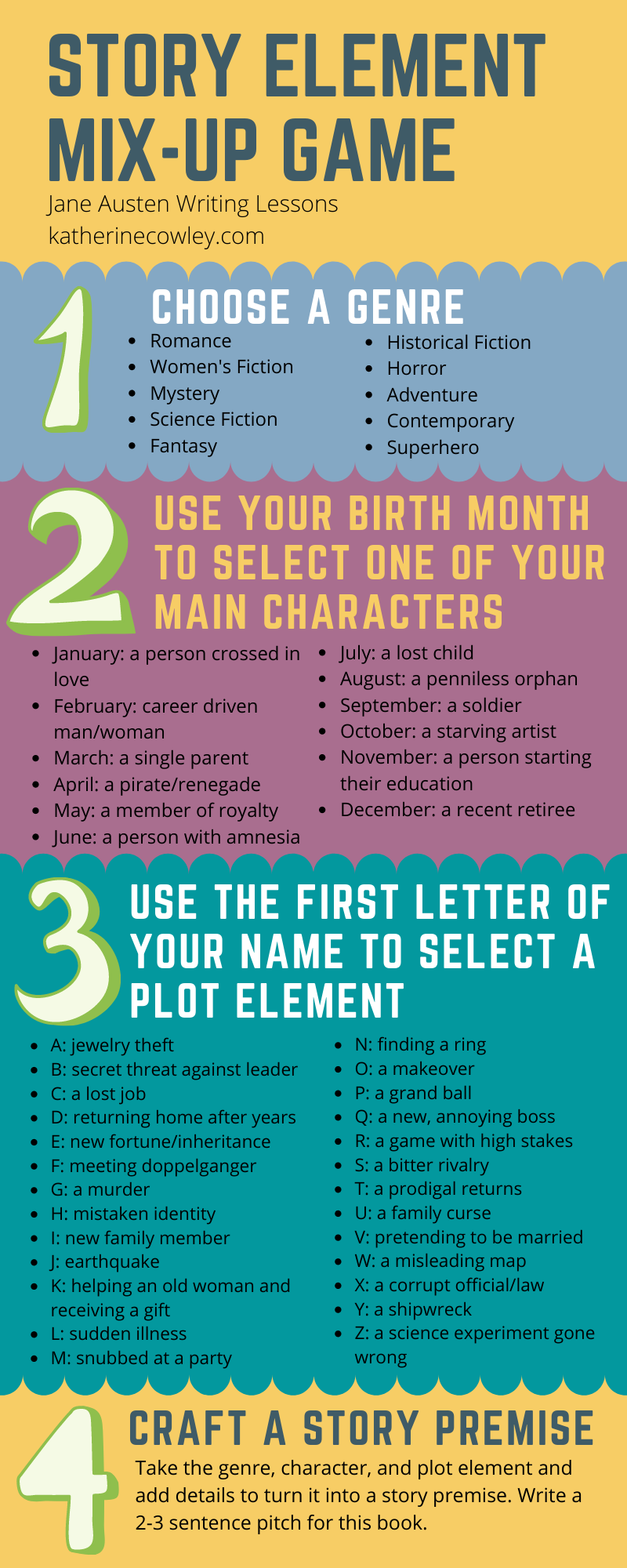

Play the story element mix-up game below. First, choose a genre, then select a main character and a plot element. Add details and craft a pitch for the story’s premise.

As an example, I have selected the following elements:

- Historical fiction

- Person crossed in love

- Helping an old woman and receiving a gift

Now I will add some additional details in order to craft a story premise:

The widow Lady Gertrude thought she had found love again, but the charming Mr. Wenton was actually a swindler who robbed her of 1000 pounds. Now she is fighting to keep her deceased husband’s estate, while struggling to help the ailing, old housekeeper, Mrs. Winter. Lady Gertrude cares for Mrs. Winter personally, and with her dying breaths Mrs. Winter tells her the location of hidden chest. Inside, Lady Gertrude discovers a family secret: a record of her deceased husband’s disinherited cousin, the scarred and troubled Colonel Anthrop, who may hold the key to saving both the estate and Lady Gertrude’s broken heart.

If you would like to do the exercise more than once, use the birth month and name of a friend, or change the genre. (Or go rogue and choose whichever elements from the chart you would like!)

If I were to create a story premise with the same components but a different genre (superhero), my story premise might look like this:

Angela moves to a small town in the upper peninsula of Michigan to escape her past—and her cheating ex-boyfriend. As she’s moving into an old, one-bedroom apartment, she helps an old woman with her groceries. The brownies the old woman gives her as a thank-you give Angela superpowers, including the ability to sense when a crime is being committed. Soon she discovers a conspiracy involving the famous Tahquamenon Falls, and Angela must use her powers to save her newfound community.

Exercise 2

Brainstorm a list of story ideas. These do not have to be fully developed story ideas—rather, they can be interesting story elements. The film director Michael Rabiger recommends keeping a CLOSAT journal, where you record interesting Characters, Locations, Objects, Situations, Acts, and Themes. These can be from life, from your imagination, from other stories or art, from the news, etc. Once you find a story element you really like, see what you can combine it with to develop a story.

Exercise 3

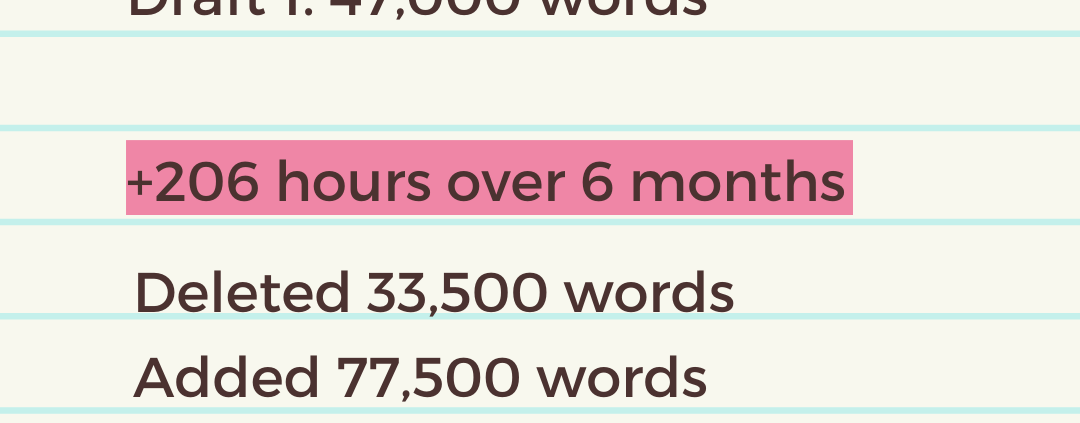

If you are already working on a short story or a novel, practice writing an elevator pitch: a short, 1-2 sentence pitch about your story that you could give to someone in the length of time you would spend with them in an elevator. Consider which core elements make your premise unique and compelling, and see if you can capture the core conflict of the story in your pitch. As a bonus challenge, pitch your story idea to five different people.