2020 In Review, and Writing like Alexander Hamilton

The time has come—the long-awaited time of year in which I interrupt your life with charts, beautiful charts!

It’s year in review time. And despite the trash fire that 2020 has been overall, it’s been a really good writing year for me.

(Now I do feel a little self-conscious about it having been a good writing year. So many people have struggled with so much this year—loss of loved ones, personal health, jobs, etc. And as a result of those things or just general 2020ness, many people who have wanted to write have found themselves unable to write. I have a friend who has dozens of published books, and she has not been able to write much this year at all. If this is what your year was like, don’t need to beat yourself up for it. There are times and seasons for everything, and if you weren’t able to write or progress towards your personal goals this year, there will be years where you can.)

And now, on to my charts.

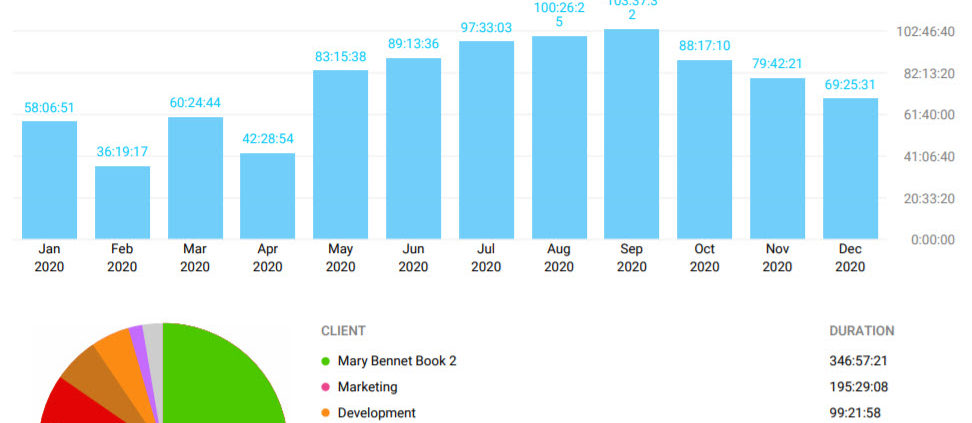

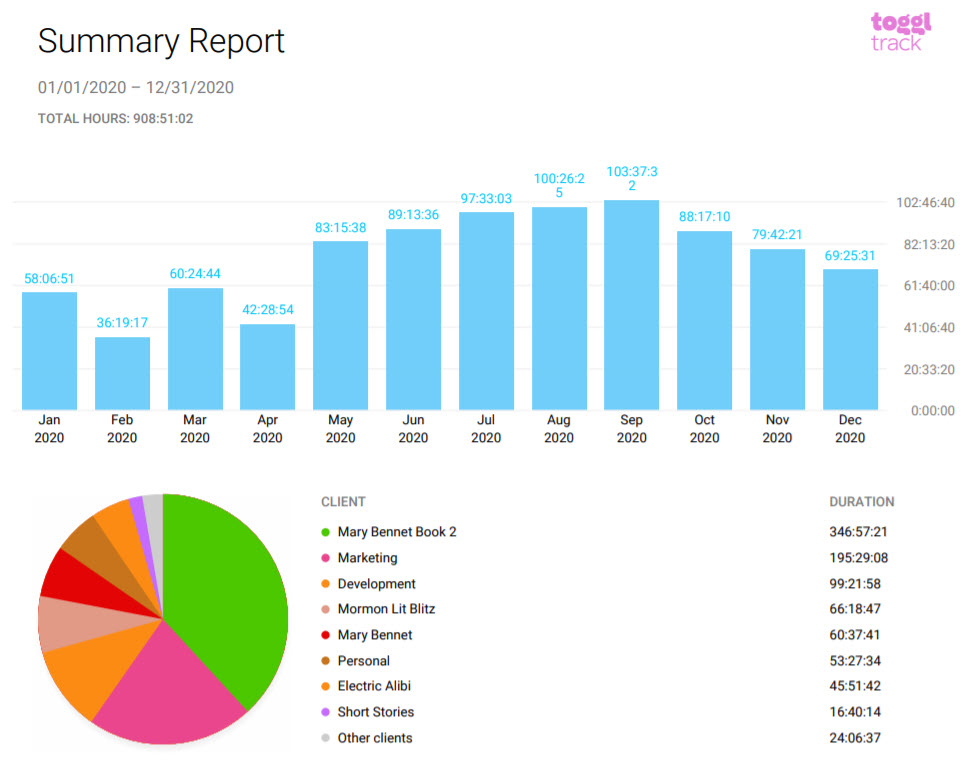

This Year I Wrote for 909 Hours

Note: by “writing” I include research, outlining, revision, planning, writing group, critiquing, listening to writing podcasts, writing accounting, etc…. For example, the “marketing” category includes a multitude of things, including my website (which I revamped this year), blog posts, writing-related social media posts, and conferences and library presentations (I gave two presentations this year). Development includes critiquing, writing group, networking, listening to writing podcasts, and reading books about writing craft.

909 hours works out to an average of 2.5 hours every single day including weekends (if you only include weekdays, it would be an average of 3.5 hours per day). So basically, it was my part-time job.

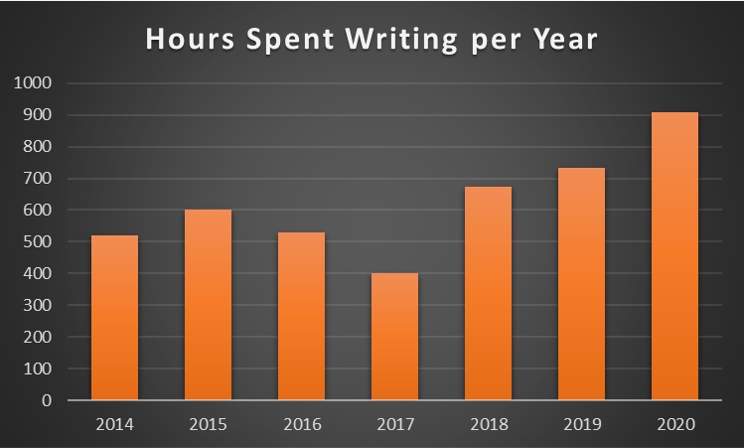

This is by far the most I have ever written in a year. As evidence, I present another chart:

The bulk of my time this year was spent working on my Mary Bennet series. (Which relates to my biggest writing news of the year—I got a three-book-deal with Tule!)

This year I spent 60 hours on the first Mary Bennet book (revisions and copy edits for Tule), 347 hours on the second Mary Bennet book (starting with the second draft, and revising it until it was ready to submit to Tule), and 9 hours on the third Mary Bennet book (this is the one I wish I had spent more on, because I really need to make progress on book 3).

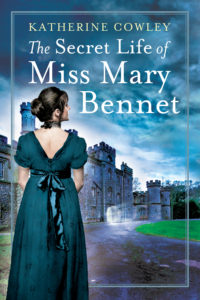

Here’s the cover of the first book, which will be out on April 22nd, 2021:

(If you use Goodreads and haven’t yet added the book to your shelves, here’s the link!)

Another task that I put a lot of hours into was my Jane Austen Writing Lessons. I spent 125 hours on them, and I feel like the posts are really useful in terms of writing craft (and writing them has been a great diversion for me—it’s refreshing to write something that’s more essay-ish rather than fiction). Interesting note—of the 94,500 new words I wrote this year, 36,500 words were on Jane Austen Writing Lessons. So I’ve basically blogged half of a nonfiction book, which is pretty cool, to be honest.

How in the World Did I Write 909 hours during a Global Pandemic?

In part, this was due to the fact that I sort of lost my job this year.

I wasn’t fired. But due to university budget constraints, I wasn’t assigned a section to teach this fall, so I’m not working, and I’m not getting paid. Because I wasn’t actually fired, I can still access the university library (including the Oxford English Dictionary online) and keep my subscription to the New York Times.

Not working has had the side effect of giving me extra hours to write.

Also, the lack of going places and doing things this year has given me extra hours. For instance, I typically write a lot less in the summer, due to driving my kids to lessons and activities, as well doing a bit of travel. Suddenly, this summer, I had a lot more time, and my kids have now hit an age where they were better at entertaining themselves and each other.

Yet the biggest reason I’ve managed to write so much is that I’ve been channeling Alexander Hamilton (or at least the Lin-Manuel Miranda version of him)

Two of my favorite lines from Hamilton are in the song “Non-Stop”:

Why do you write like you’re running out of time?

How do you write like you need it to survive?

Why do you write like you’re running out of time?

This year, I’ve felt like I’m running out of time. And I accept full responsibility for this. When my agent started pitching The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet to publishers at the beginning of the year, I already had written a first draft of the second book in the series. So I was confident that if the series was picked up by a publisher, I could revise book 2 this year.

Lo and behold, Tule acquired the entire trilogy, and in my contract listed the date by which I would submit book 2 to them. November 1st, 2020. This was the date I provided, but it ended up being a challenging date to reach.

The book needed a lot more work than I realized—it was a hard book to write, a hard year for me to resolve story problems and actually get words onto the page, and so I spent the entire year writing and revising like I was running out of time. But I made the deadline, and I’m really happy with the results!

(The thing is, I would probably set a similar deadline for myself if I was writing a new trilogy. I would just keep my fingers crossed that there wouldn’t be a global pandemic during the process of writing.)

Why do you write like you need it to survive?

Writing has been one of the things that give me joy, that makes me feel steady and centered, and that gives me purpose and direction. And it truly helped me get through this year. So yes, I need writing to survive.

That and chocolate. Does anyone have chocolate? (I’ve somehow ran out of chocolate…)

Goals for 2021

- Successful launch of my debut novel, The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet

- Write and revise Mary Bennet book 3

- Finish up a quick revision of an old steampunk mystery novel that I shelved for a few years

If I do these three things, I will be happy. (Also, I have to do the first two, because I’ve signed a contract, so…so I better go listen to some more Hamilton.)

Thanks for joining me on my writing journey!

(Also–side note. If you’re not subscribed to my newsletter, I sent out a newsletter today about how I recently deleted 100 pages from the aforementioned steampunk mystery novel. You can read about it by clicking on that link. And if you don’t want to miss future newsletters, subscribe below.)

![According to Oxford Languages, positioning is “[arranging] in a particular place or way,” or a character portraying themselves “as a particular type of person.” (Jane Austen Writing Lessons)](https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Layered-Characters-2-Small.png)