#7: Create Multiple Relationship Arcs to Show Your Character’s Journey in Relation to Those Around Them

Theatrical adaptations of Jane Austen’s novels often eliminate characters in order to shorten, to focus, and/or to interpret the story. Simon Reade’s play Pride and Prejudice eliminates Colonel Fitzwilliam. Kate Hamill’s play Pride and Prejudice eliminates not only Colonel Fitzwilliam, but also Kitty and the Gardiners. Isobel McArthur’s play Pride and Prejudice (sort of) eliminates Colonel Fitzwilliam, but adds a group of named servants: Anne, Clara, Effie, Flo, Maisie, and Tillie. Melissa Leilani Larsen’s adaptation keeps Colonel Fitzwilliam (so if you’re a Colonel fan, this is the one for you); Mrs. Gardiner is maintained as a referenced character but is never seen on stage.

When characters are eliminated in an adaptation, either plot elements must be eliminated or something or someone else must step in to serve the missing role. For instance, in the adaptations that eliminate Colonel Fitzwilliam, Elizabeth must find out through other means that Mr. Darcy separated Jane and Mr. Bingley. (In one adaptation, Darcy himself tells her.)

The chosen cast of characters heavily influences the plot of any novel. Yet characters do more than that:

Each character can help illuminate the main character and their journey for the reader.

In Pride and Prejudice, the main character is Elizabeth Bennet, and the core relationship of the story is with Mr. Darcy, because it is through their relationship that we see most of Elizabeth’s change and growth through the story. Their relationship arc is a definitive component of Elizabeth’s journey.

Elizabeth also experiences relationship arcs with a number of other characters: her relationships with these people progress, develop, change, shift, deepen, weaken, experience betrayal, are challenged, etc.

Characters who have relationship arcs with Elizabeth in Pride and Prejudice:

- Jane

- Lydia

- Charlotte Lucas

- Wickham

- Bennet

- Bennet

- Collins

- Lady Catherine de Bourgh

- The Gardiners

There are a number of other characters in the novel whose relationships with Elizabeth don’t change or have an arc over the course of the novel, including:

- Mary

- Kitty

- Phillips

- Anne de Bourgh

- Sir William Lucas

- Lady Lucas

While not all characters need to have a relationship arc with the main character, incorporating multiple relationship arcs in a story makes a richer world and makes the main character seem more complex and nuanced. Relationship arcs show your main character’s journey in relation to those around them.

(Note: There are books with a single character, or just two or three characters, but most books include more. For those books with only a few characters, these relationship arcs tend to be especially important. In short stories it is typically better to only include a handful of characters.)

Exercise 1:

Make a list of people with whom you have interacted with in the last week, either in person or otherwise (phone call, letter, digitally, etc.). Put these people into categories (friends, family, work, school, mortal enemies, acquaintances, salespeople, etc.).

Draw a star next to the three people whose relationships with you have changed or developed the most within the last month or year.

Exercise 2:

Create a list of your favorite supporting characters from books or movies. These should not be main characters, but rather small or medium characters that play a part in the story. For each character you have listed, write down a few attributes that you like about them, as well as details about their relationship with the main character. If you’re willing, share one of these characters in the comments.

Exercise 3:

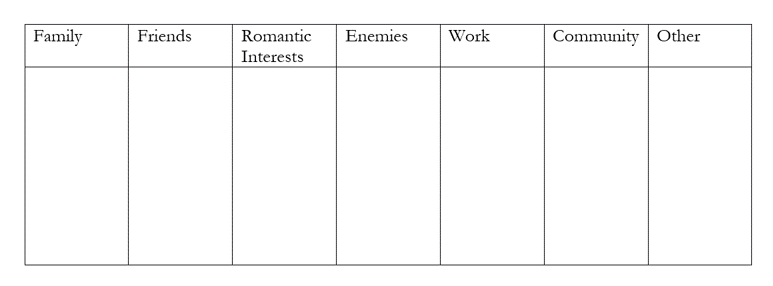

Option 1: If you are planning out a story, make a chart of character relationships that are important to your main character. This is a standard chart but can be adapted for the type of story you are telling (for example, a mystery novel should have a column titled “suspects”). Some categories may only include one person, while some categories may include a number of individuals.

It is likely that not all of these characters will be in your story, or at least not all of them will play crucial roles in the story. Some of these characters will be main characters, while others will be supporting. Underline the characters who will be most instrumental to the plot, and highlight the characters who will have the most important relationship arcs with the main character.

Option 2: If you are revising a story, use Excel, Google Spreadsheets, or paper and pen to chart your characters over the course of your novel. One way to do this is to put an “X” for every time they are seen in a chapter and an “x” for every time they are mentioned. Another way to do this is to write a brief description of the role each character plays in each chapter. Here’s a sample of what it might look like if I was tracking characters in the first few chapters of Pride and Prejudice.

Once you’ve completed your chart, you can use it to self-diagnose areas where you can improve. For example, if one of your characters is supposed to have an important relationship arc but they are not present for a six-chapter segment, that could be an important thing to incorporate in your revisions.