#17: Make Your Characters Active

In 2012 I created a daily video blog, where every single day I posted a five to thirty second video of something interesting. As I worked on this project, I discovered that only certain categories of things would work for the project:

- A still shot (the camera not moving) with something moving inside the frame

- A moving shot (the camera moving) with something moving inside the frame

- A moving shot (the camera moving) with still objects

The only other option—a still shot with nothing moving—was not actually an option. Because that would be a photograph, not a video.

I quickly discovered that the best videos fit in categories 1 or 2. If something was moving in the frame, it attracted interested, regardless of what I did with the camera. (As a side note, my main claim to internet fame is that Day 119 of my blog—which features a DVD screensaver hitting the corner of the TV screen—has been viewed over 50,000 times.)

Our eyes are drawn immediately to things in motion. Our eyes, and often our hearts. This is the power of using active characters.

Readers are drawn to active characters. Active characters are doing. Outside things may happen to them, but they are not just observers or reactors. They do not let themselves be pushed around or be determined by others. They go, they do, they strive.

Making your protagonist an active character creates a powerful story. This propels them on an external journey, through the plot, with all its outward struggle and growth. It also propels them through an internal journey, facilitating character development, with its inner struggle and growth.

Both of the female leads in Sense and Sensibility—the two oldest Dashwood sisters—are active characters. The eldest sister, Elinor, is active—she steers her mother away from renting too expensive of a house, and she does much to ease the pain of others and make their cottage a home. The middle sister, Marianne, is active in a different direction.

Marianne refuses to let others play matchmaker with her future and is guided by her own opinions and philosophies. (Unlike Elinor, she is unafraid of offending others, and not held back by a strong sense of decorum.) She is energetic, and attempts to find and make beauty in the world.

Their cottage is in a beautiful countryside, and on a somewhat blustery day, Marianne encourages her younger sister Margaret to walk with her:

They gaily ascended the downs, rejoicing in their own penetration at every glimpse of blue sky; and when they caught in their faces the animating gales of a high south-westerly wind, they pitied the fears which had prevented their mother and Elinor from sharing such delightful sensations.

“Is there a felicity in the world,” said Marianne, “superior to this?—Margaret, we will walk here at least two hours.”

Their walk, however, is cut short by the driving rain. Marianne is an active character, in charge of her own destiny, but even she cannot prevent the weather. Yet even in reacting to the weather, she resists passivity:

Chagrined and surprised, they were obliged, though unwillingly, to turn back, for no shelter was nearer than their own house. One consolation however remained for them, to which the exigence of the moment gave more than usual propriety; it was that of running with all possible speed down the steep side of the hill which led immediately to their garden gate.

Marianne is delightful because of her energy, her joyous outlook on life, and her refusal to do things in a simple, boring way.

As a result of her action, she hurts her ankle on the hill, and is rescued by a charming gentleman, Mr. Willoughby, who carries her home.

Over the coming chapters, Marianne becomes quite attached to Willoughby. This worries Elinor, who actively encourages Marianne to be more careful with her affections, particularly with how they might be interpreted by others outside of their family. Marianne actively resists Elinor’s advice, and responds:

“You are mistaken, Elinor,” said she warmly, “in supposing I know very little of Willoughby. I have not known him long indeed, but I am much better acquainted with him, than I am with any other creature in the world, except yourself and mama. It is not time or opportunity that is to determine intimacy;—it is disposition alone. Seven years would be insufficient to make some people acquainted with each other, and seven days are more than enough for others. I should hold myself guilty of greater impropriety in accepting a horse from my brother, than from Willoughby. Of John I know very little, though we have lived together for years; but of Willoughby my judgment has long been formed.”

What are the marks of an active character?

An active character:

An active character can be bold or shy, outspoken or quiet, and their actions can be grand or minute. But something internal propels them forward.

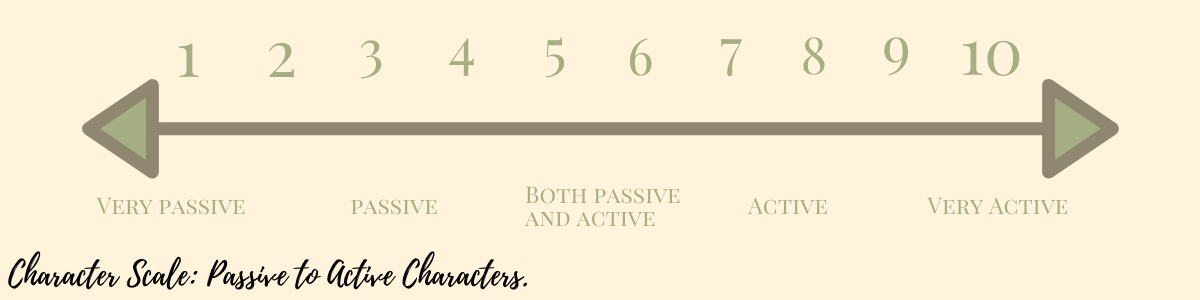

Yet no character is fully active, and as writers, we shouldn’t consider it a dichotomous choice between active and passive characters. No character is active all of the time—nor should they be. This movement along the spectrum of active and passive can be powerful.

Later on in Sense and Sensibility, Marianne falls into a deep depression, and becomes a largely inactive character. Her moments of activity—like taking a walk in bad weather—do her more harm than good. She becomes ill, which forces further inactivity upon her: at this point it is the doctor’s treatment and fate which determine her future.

Yet the fact that Marianne is generally an active character both creates audience investment in her and helps drive the story forward. Then, in these moments of passivity, we still root for her.

Exercise 1: The following passage focuses on a passive character:

“You want vanilla?” asked George.

Rudy nodded at her brother. “Sure.” Vanilla was as good as any other flavor.

George ordered and paid. “My treat,” he said. “It’s been way too long.”

“Thanks,” said Rudy.

The server gave them their ice cream and they sat down to a table.

“How’s work going?” asked Rudy.

He told stories about his adventures as a plumber, and some of the crazy things he learned about people’s personal lives.

“How’s work going for you?” asked George.

“Same as always,” said Rudy.

George’s phone rang. He looked at the screen. “Mind if I take this?”

“Not at all.”

He stepped out of the ice cream shop.

Rudy looked around the restaurant at the happy families, happy couples. There was only one person sitting alone, a man about her age. He made eye contact, and she looked down, pretending she hadn’t noticed.

Rewrite the passage to make Rudy a more active character. You could make her more active throughout, or in just one section of the scene. Also, feel free to take the scene in a different direction.

Exercise 2: Read a book or watch a film and analyze the text for active and passive characters. Who is passive? Who is active? Are there moments when characters become more passive or more active, and what is the result? As you analyze, pay particular attention to the protagonist.

Exercise 3: If you’ve drafted a novel or as short story, analyze each scene/chapter for where your main character falls on the spectrum from active to passive. Assign each scene a number from 1 to 10 on a passive to active scale. For the purposes of this exercise, use 10 to mean a character is extremely active, a 7 or 8 for active, a 5 or 6 for scenes with both active and passive elements, a 3 for passive, and a 1 for extremely passive.

What sort of arc or movement is created by the main character’s movement along the passive-active spectrum? Are there scenes where your character should be more active? Where your character should be more passive? Where your character should be wrestling with both active and passive tendencies in themselves?