#66: Evoking Emotions Through Objective Correlative (External Objects)

A powerful way to evoke emotions—to make them feel real, material, and defined—is through the use of objective correlative, or using external objects that the reader connects with an emotion. And of course, Jane Austen is a master at this.

In Austen’s novel Emma, the character of Harriet has difficulties with love (largely because of Emma’s interference). She becomes head-over-heels for Mr. Elton, and is devastated when she learns that he is not interested in her. Mr. Elton leaves town for a time period, and comes back with a bride, Augusta Hawkins. A few months later, a ball is held, and even though it is tradition for married men to dance with the unmarried ladies, Harriet is snubbed by Mr. Elton.

After the ball, Harriet comes to visit Emma, bringing with her a parcel on which she has written “Most precious treasures.” She wants to destroy these treasures, and she wants Emma as a witness.

Inside are two objects. First, is court plaister which Mr. Elton had once played with. Dictionary.com defines court plaister as “cotton or other fabric coated on one side with an adhesive preparation, as of isinglass and glycerin, used on the skin for medical and cosmetic purposes.” In essence, Harriet has kept an expensive Band-Aid.

The other object is a “superior treasure,” for Harriet finds it even “more valuable, because this is what did really once belong to him.”

She reveals the object to Emma:

It was the end of an old pencil,—the part without any lead.

Harriet has kept Mr. Elton’s pencil for months after his marriage to someone else. The tiny end of an old pencil stub, without any lead—it’s an evocative image, conjuring up a series of emotions for the reader. We feel pity for Harriet, we feel sympathy for her love and her heartbreak as we understand the depth of her feelings, and we feel negatively towards Emma. After all, it is Emma’s interference which has caused all this, has caused a discarded pencil stub to be another woman’s most prized possession.

This is a classic use of objective correlative.

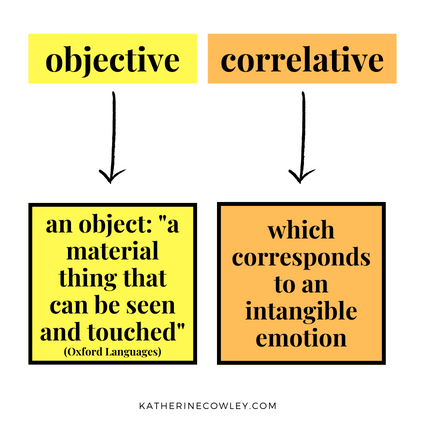

Defining Objective Correlative and Its Powerful Emotional Impacts

According to scholar George P. Winston, the term objective correlative was coined by the American painter Washington Allston in 1843.

Allston’s definition of objective correlative is rather opaque. In his book Lectures on Art, he talks about how cabbages are different than cauliflowers—a cabbage can’t just change into a cauliflower, for it is a cabbage, and has its own physical properties and meaning.

Picture of a woman experiencing emotions while accompanied by cabbage and cauliflower (and broccoli). Washington Allston would approve. Photo by Ivan Samkov from Pexels.

Then Allston writes:

So, too, is the external world to the mind; which needs, also, as the condition of its manifestation, its objective correlative. Hence the presence of some outward object, predetermined to correspond to the preëxisting idea in its living power, is essential to the evolution of its proper end,–the pleasurable emotion.

In other words, the things that happen inside our heads—and I would like to add, inside our hearts—are difficult to understand or to manifest. It’s so easy to go about our days and not understand why people are making the choices they’re making. It’s so easy to feel like others don’t truly understand our emotions—or that we don’t truly understand the emotions of those around us.

This becomes tricky for the writer. How do we take an emotion, something which is inherently abstract, intangible, and in many senses, undefinable, and make it feel real and substantial to the reader? There are numerous techniques that writers, including Jane Austen, use, including body language, facial expressions, dialogue, silence, free indirect speech, punctuation, syntax, repetition, and physical sensation, to name a few.

Allston doesn’t address these approaches, in part because he is a painter, interested in things which can take visual, material form on the canvas. But his advice can be useful for writers as well: he says that what we need do is manifest the mind—manifest the internal, unfathomable emotion—by finding a concrete, external object that can correlate to what is happening on the inside.

For Washington Allston, objects are “predetermined to correspond” to a “preexisting idea” or emotion, and I agree that there are some objects that have a standard emotion that are attached to them. For instance, in Western culture a coffin often evokes emotions related to sadness and mourning.

Yet we don’t automatically associate a pencil stub with the powerful emotions that Jane Austen conveys through it. So in order see the true power of objective correlative, we need a more expansive definition.

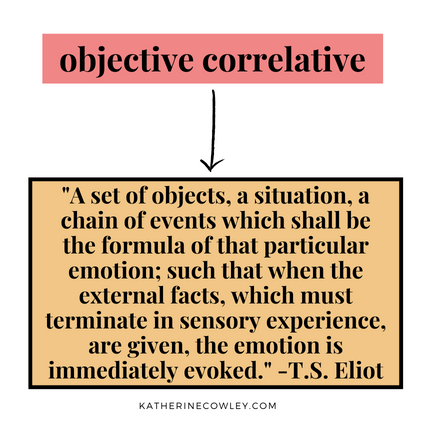

While others used Allston’s term, it was T.S. Eliot who popularized it in his 1919 essay, “Hamlet and His Problems.” He writes:

The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an “objective correlative”; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked.

For T.S. Eliot, the emotional meaning of the object is contextual—it’s dependent on what happens around it in the poem or story. Objects are part of a situation and a chain of events, and it these groupings which create a formula for a particular emotion.

Let’s consider a few more examples of objective correlative in Austen’s work to see how we can apply this to our own writing.

In Sense and Sensibility, Marianne sees and reflects on the dead leaves with all the passion of romanticism. The leaves embody Marianne’s endless emotions and grief as she loses her home. The podcast The Thing About Austen has an excellent episode on Marianne’s dead leaves.

In Mansfield Park, the play Lovers’ Vows becomes an object which conveys emotions, both of Fanny and the other characters. This is truly a set of objects: there’s the script itself, the assignment of roles, all the preparations, and of course the physical set which is built and then torn down by Fanny’s uncle, leaving the play unperformed.

In the uncompleted novel Sanditon, the characters drive past Mr. and Mrs. Parker’s old house on the outskirts of Sanditon, which they have left in order to live in a new house, in the heart of the action, so they can pursue Mr. Parker’s dreams for Sanditon. Both Mr. and Mrs. Parker see different things in the old house and its gardens—they notice different attributes, and the things they notice and comment upon reveal that they feel very differently about the past, present, and future. While Mr. Parker praises it as “the house of my forefathers,” he remarks that it is “built in a hole” and that he is happy to have moved on. Mrs. Parker, on the other hand, says that it was a “very comfortable house,” and notices the beautiful garden, the places for the children to run and play, the desirable shade, and how it is always sheltered from the effects of winds and storms. It is clear that she misses the house and wishes they could return to it, and it is clear that turning Sanditon into a resort town is her husband’s dream, not hers.

It is important to note that Jane Austen uses objective correlative with moderation. None of her novels are packed with objective correlative, and not every object included in the novels is meant to create an emotion. Yet when she does use it, she does so to great effect.

How to Use Objective Correlative to Convey Emotions in Fiction

There are a number of principles we can take from how Jane Austen uses objective correlative:

- Objects can be used to correspond to emotions large and small.

- Some objects are important or evocative in their own right, but many are made important by the attention given to them. The context and history of the object can also help imbue meaning.

- In crafting fiction, it’s important to consider what people do with the objects or how they interact or talk about them.

- Highlighting the characteristics or attributes of an object can help open up our understanding of the corresponding emotion.

- The same object can engender different emotions for different characters. While sometimes an object reveals only the emotions of the main character, it can also reveal the emotions of other characters in the story.

- An object can be used in a single scene (like the pencil in Emma), or in sequence of scenes (like the play in Mansfield Park).

- In addition to revealing the emotions of characters, objects can create emotions in the reader.

I want to use one more example from Austen, to further explore the last two points: how an object can be used in a sequence of scenes, and how an object can create emotions in the reader.

Using Objective Correlative to Build to Moments of Emotional Weight for the Reader

In his definition, T.S. Eliot talked about a SET of objects and a CHAIN of events which immediately evoke a particular emotion in the audience.

One of the most effective ways to create a strong emotion in a reader is to build emotion with an object over time.

A great example of this is in Sense and Sensibility. (Warning: there will be major spoilers for the novel below!) As discussed in a previous post, Elinor keeps her emotions mostly inside. So how do we know that she is feeling strongly, and how do we as readers feel strongly with her? And how can we as readers draw parallels between Elinor’s heartbreak and her sister’s heartbreak, even though they are both such different characters? Austen achieves all of this through objective correlative.

The objects used by Austen are locks of hair.

Locks of hair inlaid in a pearl bracelet. This piece was made in England between 1790 and 1810, and is owned by the Walters Art Museum. Image used through Creative Commons license.

Austen sets up these objects early on in the novel as meaningful tokens of affection when young Margaret tells Elinor that she saw Willoughby take a lock of Marianne’s hair:

Last night after tea, when you and mama went out of the room, they were whispering and talking together as fast as could be, and he seemed to be begging something of her, and presently he took up her scissors and cut off a long lock of her hair, for it was all tumbled down her back; and he kissed it, and folded it up in a piece of white paper; and put it into his pocket-book.

In a later chapter, the man Elinor loves, Edward, comes to visit. He is wearing a ring which contains a lock of hair. Marianne immediately assumes it belongs to Elinor, and teases Edward by pretending to wonder if the hair belongs to Edward’s sister, Fanny:

[Marianne] was sitting by Edward, and in taking his tea from Mrs. Dashwood, his hand passed so directly before her, as to make a ring, with a plait of hair in the centre, very conspicuous on one of his fingers.

“I never saw you wear a ring before, Edward,” she cried. “Is that Fanny’s hair? I remember her promising to give you some. But I should have thought her hair had been darker.”

Marianne spoke inconsiderately what she really felt—but when she saw how much she had pained Edward, her own vexation at her want of thought could not be surpassed by his. He coloured very deeply, and giving a momentary glance at Elinor, replied, “Yes; it is my sister’s hair. The setting always casts a different shade on it, you know.”

Elinor had met his eye, and looked conscious likewise. That the hair was her own, she instantaneously felt as well satisfied as Marianne; the only difference in their conclusions was, that what Marianne considered as a free gift from her sister, Elinor was conscious must have been procured by some theft or contrivance unknown to herself. She was not in a humour, however, to regard it as an affront, and affecting to take no notice of what passed, by instantly talking of something else, she internally resolved henceforward to catch every opportunity of eyeing the hair and of satisfying herself, beyond all doubt, that it was exactly the shade of her own.

Edward’s embarrassment lasted some time, and it ended in an absence of mind still more settled. He was particularly grave the whole morning. Marianne severely censured herself for what she had said; but her own forgiveness might have been more speedy, had she known how little offence it had given her sister.

Elinor is secretly pleased that Edward wears her hair in a ring. This is a promise of hope, a promise of affection, a promise that someday they might wed. And all of this emotion is embodied in a lock of hair.

A memorial ring from 1804 or 1805 with locks of hair set between pearls. Mourning rings were given out to family and close friends at funerals, and often included locks of hair. In Sense and Sensibility it is clear that a ring with a lock of hair was not assumed to be a mourning ring, and that it was quite common for the ring to commemorate a living person. This ring is also owned by the Walters Art Museum. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

A few chapters later, as the chain of events progresses, Austen once again uses this same lock of hair. This is the prime example of what T.S. Eliot’s emotional formula, for she has set up the object to produce a very specific emotion from the reader.

What happens is that Elinor meets Lucy Steele. Lucy deduces that Elinor is in love with Edward, but Lucy is also in love with Edward, and she wants to mark her territory.

Lucy makes Elinor promise not to tell anyone what she is about to share, and then she confides in Elinor that she has been secretly engaged to Edward for four years.

Elinor cannot believe her, but Lucy provides more and more evidence, including dates and places that align with Elinor’s knowledge of Edward’s whereabouts, a miniature painting of Edward, and a letter written in Edward’s hand.

Then Lucy manages to completely decimate both Elinor and the reader’s emotions by bringing back a reference to the key object:

“Writing to each other,” said Lucy, returning the letter into her pocket, “is the only comfort we have in such long separations. Yes, I have one other comfort in his picture, but poor Edward has not even that. If he had but my picture, he says he should be easy. I gave him a lock of my hair set in a ring when he was at Longstaple last, and that was some comfort to him, he said, but not equal to a picture. Perhaps you might notice the ring when you saw him?”

“I did,” said Elinor, with a composure of voice, under which was concealed an emotion and distress beyond any thing she had ever felt before. She was mortified, shocked, confounded.

We too are mortified, shocked, and confounded, and we feel it deeply because these emotions are attached to a physical object. We thought the ring and the hair meant one thing, and to discover without a doubt that it means something else—this immediately evokes a reaction.

For me, this is the most powerful use of objective correlative in Sense and Sensibility, yet Austen continues to use locks of hair for emotional effect by bringing back the other lock of hair: Marianne’s.

When Marianne and Elinor spend the season in London, Marianne is snubbed by her love, Willoughby, and Elinor finds Marianne on her bed, completely and “violently” distraught. Next to Marianne, she discovers a letter from Willoughby, who has returned Marianne’s lock of hair.

It is with great regret that I obey your commands in returning the letters with which I have been honoured from you, and the lock of hair, which you so obligingly bestowed on me.

Marianne had asked for her letters and the lock of hair back, “if your sentiments are no longer what they were.” But she did not actually want him to return the hair. As she tells Elinor, she thought they were engaged:

“I felt myself,” she added, “to be as solemnly engaged to him, as if the strictest legal covenant had bound us to each other.”

“I can believe it,” said Elinor; “but unfortunately he did not feel the same.”

“He did feel the same, Elinor—for weeks and weeks he felt it. I know he did. Whatever may have changed him now, (and nothing but the blackest art employed against me can have done it), I was once as dear to him as my own soul could wish. This lock of hair, which now he can so readily give up, was begged of me with the most earnest supplication. Had you seen his look, his manner, had you heard his voice at that moment!”

Marianne rereads Willoughby’s letter, and the reference to the lock of hair only makes her more upset:

“It is too much! Oh, Willoughby, Willoughby, could this be yours! Cruel, cruel—nothing can acquit you….‘The lock of hair, (repeating it from the letter,) which you so obligingly bestowed on me’—That is unpardonable. Willoughby, where was your heart when you wrote those words? Oh, barbarously insolent!—Elinor, can he be justified?”

Once again, Austen employs objective correlative to show the depth of Marianne’s emotion by attaching it to a physical object. And, like Elinor, we feel deeply for Marianne.

Having built up this chain of events, with this set of objects (the locks of hair), Jane Austen continues to use them to great effect, bringing up each lock of hair one additional time.

When Marianne is severely ill and almost dies, Willoughby comes to visit, and tries to justify and redeem himself to Elinor. He blames his fiancé for forcing him to break Marianne’s heart and return Marianne’s lock of hair.

“[Marianne’s] three notes,—unluckily they were all in my pocketbook, or I should have denied their existence, and hoarded them for ever,—I was forced to put them up, and could not even kiss them. And the lock of hair—that too I had always carried about me in the same pocket-book, which was now searched by Madam with the most ingratiating virulence,—the dear lock,—all, every memento was torn from me.”

Elinor is tempted to absolve Willoughby—his speech is long and passionate, and the way he talks about Marianne’s lock of hair is definitely a point in his favor. Yet he returned it and broke his heart (and behaved like a rascal in other ways).

A brooch containing hair, so you can wear someone’s hair in your own hair. This was made in the 19th century, and is part of the permanent collection of The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Finally, Lucy’s lock of hair is once again brought back. After marrying Edward’s brother, she writes one last letter to Edward, saying that she feels no ill will to him, and that she decided that she could bestow her affections elsewhere since she thought she had lost his. The postscript of the letter reads:

“I have burnt all your letters, and will return your picture the first opportunity. Please to destroy my scrawls—but the ring with my hair you are very welcome to keep.”

Oh, dear Lucy. You are married to Edward’s brother, but you want him to keep your lock of hair. You want him to treasure and remember you still.

In this case, Austen is creating a very different emotion. We are meant to laugh at Lucy—and this becomes a laugh of relief, and we do feel relief, for Edward and Elinor have finally been able to come together. Edward and Elinor are able to read the letter and move past it. As Shakespeare would say, “All’s well that ends well.”

Jane Austen does not reveal what Edward actually does with the ring and the lock of hair, but based on his words to Elinor, and what that lock of hair meant to Lucy, we can safely assume that he does not keep it.

It amazes me what a simple lock of hair can do in the hands of an author like Jane Austen. This is my favorite example of objective correlative in literature.

There will be one more Jane Austen writing lesson to wrap up the series on emotion—I will be talking about other ways to build emotion across multiple scenes. And as always, there are three writing exercises below.

Exercise 1: Think of a scene you have written that has an important emotion (the emotion can be important, whether it is a large or a small one). Now imagine that you’re a painter. Instead of painting the character with their facial expression, you’ve decided to paint an object that corresponds to their emotion. If you have artistic inclinations (or want to try something new), paint or draw a picture of the object. If not, search for images online to find a representation of the object that best captures your character’s emotions.

Exercise 2: Reread one of your favorite stories or rewatch one of your favorite shows. Find an example of objective correlative. Is the object used once or as part of a sequence? What is the character’s relationship with the object? What emotions does the object reveal, and what emotions does the object create in the audience?

Exercise 3: For a story idea that is either new or in early stages of development/writing, choose an object or set of objects that could be used in a sequence of scenes to create emotions for the reader. Try to use the object at least three times. What does the object mean to the characters? What do you want the object to mean for the readers?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!