#64: The Size or Degree of Character Emotions

When we talk about emotions in writing, we often think of big emotions, when characters are very emotional and emotive.

Yet characters experience not only a broad range of types of emotions, but a broad range of sizes of emotions. Characters have emotions that are strong or overwhelming, but they also have emotions that are fleeting and less consequential.

When considering the size of the emotion, it’s useful to ask:

- To what degree does your character experience this emotion?

- How important is this emotion to the story?

- How many emotional clues need to be planted to convey this emotion?

In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth experiences emotions in every scene—and in most scenes, she experiences more than one emotion. Let’s look at how Jane Austen conveys small emotions, mid-size emotions, and large emotions for this character.

Small Emotions

Small emotions are ones that the character experiences either for a short time, or only to a small degree. This might a small annoyance, a temporary flush of joy, a reaction to another character or something that happened.

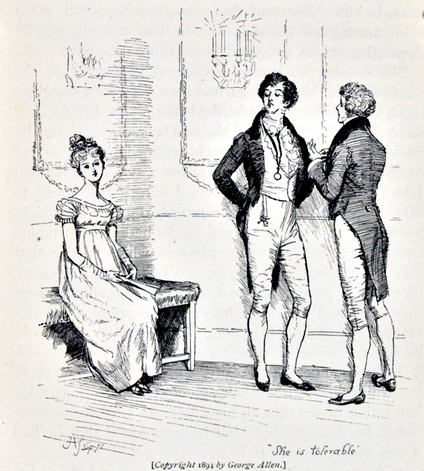

While attending the Meryton Assembly, Elizabeth overhears Mr. Bingley trying to convince Mr. Darcy to dance, and Bingley points out that Elizabeth could be a good partner. Mr. Darcy replies:

“She is tolerable; but not handsome enough to tempt me.”

1894 illustration from Pride and Prejudice by Hugh Thomson, via Lilly Library, Indiana University, Wikipedia Commons

While this is a rather weighty insult, Elizabeth has only a small emotional response:

Mr. Darcy walked off; and Elizabeth remained with no very cordial feelings towards him. She told the story however with great spirit among her friends; for she had a lively, playful disposition, which delighted in any thing ridiculous.

Clearly she’s not happy with Darcy, but rather than wallowing in the emotion, she sees it as ridiculous and tells it as a funny story.

Throughout Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth often uses humor as a lens to deal with small emotions. For some character, this event could create a much larger emotional response, but for Elizabeth it remains small, and she moves on.

It is a key emotional moment for the reader–one of the most memorable moments in the novel, that sets up their antagonism–but it doesn’t require very much space on the page.

At other times emotions are implied or are barely brushed upon. It’s important for the reader to understand what the character’s emotion is, but it’s a small emotion that needs only a small amount of space.

For example, after Mr. Collins’ arrival, he starts showering compliments on the family:

He had not been long seated before he complimented Mrs. Bennet on having so fine a family of daughters, said he had heard much of their beauty, but that, in this instance, fame had fallen short of the truth; and added, that the did not doubt her seeing them all in due time well disposed of in marriage.

And then, Austen gives us the emotional response of Elizabeth and her sisters, in contrast to Mrs. Bennet’s response:

This gallantry was not much to the taste of some of his hearers, but Mrs. Bennet, who quarrelled with no compliments, answered most readily.

It’s a simple phrase—“not much to the taste of some of his hearers”—but it does all that is needed to do to establish Elizabeth’s sentiments towards her cousin.

1894 illustration by Hugh Thomson from Pride and Prejudice. Jane, of course, is “Not for Sale,” but Mr. Collins is welcome (according to Mrs. Bennet) to choose any of the other daughters. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Mid-Size Emotions

Mid-size emotions are ones that are larger for the character. They occupy more of the character’s heart and mind—they linger, have consequence, or are not as quickly resolved. They have a weightier impact on the character, and they often require more sentences on the page—more emotional clues.

In Pride and Prejudice, after Elizabeth and her sisters meet Mr. Wickham, Mr. Bingley and Mr. Darcy see them—and Mr. Darcy sees Mr. Wickham. Elizabeth witnesses their emotions, and has her own emotions (particularly her curiosity) piqued.

[Mr. Darcy’s eyes] were suddenly arrested by the sight of the stranger, and Elizabeth happening to see the countenance of both as they looked at each other, was all astonishment at the effect of the meeting. Both changed colour, one looked white, the other red. Mr. Wickham, after a few moments, touched his hat—a salutation which Mr. Darcy just deigned to return. What could be the meaning of it? It was impossible to imagine; it was impossible not to long to know.

Here, Elizabeth notes the interaction, and her questions and her longing to know show her curiosity.

Later on in the scene, we read:

As they walked home, Elizabeth related to Jane what she had seen pass between the two gentlemen; but though Jane would have defended either or both, had they appeared to be in the wrong, she could no more explain such behaviour than her sister.

Elizabeth comes back to her emotion, she comes back to her puzzlement and her curiosity by raising it with Jane.

Mid-size emotions often need either more emotional clues, or recur again at some point in the scene.

1895 illustration by C.E. Brock of the arrival of Mr. Wickham and other officers at a gathering held by the Phillips family. Via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s not long after this point when Mr. Wickham’s confides in Elizabeth, telling his story of how he has been wronged by Mr. Darcy. This revelation produces emotions in Elizabeth that are larger than the emotions she felt upon seeing their initial antagonism, but still mid-sized in comparison to some of her emotions in other scenes.

Elizabeth is shocked, and we see this shock and surprise in her speech:

“This is quite shocking!—He deserves to be publicly disgraced.”

In the scene that follows she then asks follow-up questions. She pauses when speaking. She reflects. She remembers things Mr. Darcy has said in the past that would seem to corroborate Wickham’s claims. These emotional clues are layered on each other, giving a sense of how she feels.

She also uses many more exclamation marks than in her normal dialogue, and uses strong word choice:

“How strange!” cried Elizabeth. “How abominable! I wonder that the very pride of this Mr. Darcy has not made him just to you! If from no better motive, that he should not have been too proud to be dishonest—for dishonesty I must call it.”

Even once her conversation with Mr. Wickham is over, she keeps returning to it in her mind. Her emotions on the matter, and on Mr. Wickham more generally, become her entire focus:

There could be no conversation in the noise of Mrs. Phillips’s supper party, but his manners recommended him to everybody. Whatever he said, was said well; and whatever he did, done gracefully. Elizabeth went away with her head full of him. She could think of nothing but of Mr. Wickham, and of what he had told her, all the way home; but there was not time for her even to mention his name as they went, for neither Lydia nor Mr. Collins were once silent.

And her emotions don’t end in this scene. The next chapter begins:

Elizabeth related to Jane the next day, what had passed between Mr. Wickham and herself.

Note how much more page time is given to this emotion than to when Mr. Darcy insulted her at the ball. Note how much more it consumes her—how it engages her in different ways and uses a larger variety of emotional clues.

Large Emotions

Large emotions are bigger for the characters. They are often more personal and have larger consequences. They can accompany events or knowledge which is life changing or life shattering. Often these emotions are large because the circumstances require the character to develop a new understanding of the world and their place in it.

Like with mid-size emotions, large emotions require more page time, a layering of emotional clues, and a return, multiple times, to the emotion. Large emotions also provoke stronger reactions, stronger or more extreme physical sensations, and lead the character to engage in behavior that is outside of their norm.

1894 illustration by Hugh Thomson of Colonel Fitzwilliam and Elizabeth. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Elizabeth is extremely upset when she finds out from Colonel Fitzwilliam that it was Mr. Darcy who broke up Mr. Bingley and her sister Jane. He says simply,

“There were some strong objections against the lady.”

Paragraphs follow in which Elizabeth deals with her emotions, thinking about what happened. She considers how in some ways Mr. Darcy is right to have objections, but then she counters her own thoughts by thinking about how much Jane has been wronged.

The agitation and tears which the subject occasioned, brought on a headache; and it grew so much worse towards the evening that, added to her unwillingness to see Mr. Darcy, it determined her not to attend her cousins to Rosings, where they were engaged to drink tea.

For most of her smaller negative emotions, Elizabeth has used humor. For mid-sized ones, she grapples with the problem, considering it from many sides—which she also does here. But this is emotion to a new degree. This has caused tears and a headache. And while Elizabeth is normally very correct in her behaviors and social expectations, she does not go to Rosings as she normally would.

In the next chapter we see the continuation of this emotion as she goes through all of Jane’s letters, trying to read Jane’s emotions and see how Mr. Bingley’s absence has impacted her sister.

It’s only a few pages later that Mr. Darcy proposes to her. She angrily turns him down, expressing her emotions to him in multiple ways. Even after he has gone, we continue to experience her emotions with her, and we have a longer shift into free indirect speech than we’ve experienced at other points in the novel.

The tumult of her mind, was now painfully great. She knew not how to support herself, and from actual weakness sat down and cried for half-an-hour. Her astonishment, as she reflected on what had passed, was increased by every review of it. That she should receive an offer of marriage from Mr. Darcy! That he should have been in love with her for so many months! So much in love as to wish to marry her in spite of all the objections which had made him prevent his friend’s marrying her sister, and which must appear at least with equal force in his own case—was almost incredible! It was gratifying to have inspired unconsciously so strong an affection. But his pride, his abominable pride—his shameless avowal of what he had done with respect to Jane—his unpardonable assurance in acknowledging, though he could not justify it, and the unfeeling manner in which he had mentioned Mr. Wickham, his cruelty towards whom he had not attempted to deny, soon overcame the pity which the consideration of his attachment had for a moment excited.

She continued in very agitated reflections till the sound of Lady Catherine’s carriage made her feel how unequal she was to encounter Charlotte’s observation, and hurried her away to her room.

1895 illustration by C.E. Brock of Mr. Darcy giving Elizabeth a letter. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Later, she receives his letter full of explanations. During the letter, we just read it with Elizabeth–the whole letter is included with no interruptions, no character actions or thoughts. We experience our own emotions as readers, and can guess at Elizabeth’s. Then after the letter, we have lengthy passages in which she walks, she re-reads, she analyzes specific phrases, she reflects. Her emotions undergo multiple shifts—and we go with her through these shifts.

Large emotions are often more complicated. They are not as clear cut—anger, joy, frustration, forgiveness can all be complicated and filled with nuance. Large emotions are bottles filled to bursting, and often require the character’s exploration and the narrator’s. They shift, they grow, they lessen, they increase again, and as we ride this roller coaster with the character, we empathize and at times even have a cathartic experience.

Conclusion

If you attend a symphony, you will not hear all the instruments playing at full volume the entire time. That would not be good music. Instead, some movements may be performed at quietly, while others will swell to fortissimo, some sections may highlight the violins, while others may feature brass instruments, and other still use a solo. We may only hear the cymbal a handful of times, but when we do, it will be at key moments.

We should do the same when we write character emotions: include a range of emotions, some of which are focused on at different times. Sometimes we touch on an emotion for only a moment; other times we explore the emotion for an extended period, or bring back an emotional theme later in the story. Including varying degrees of emotions—small, mid-sized, and large—creates contrast and emphasis, directs the readers’ attention, and serves to better illustrate character, as we see how they react and change in moments big and small.

Exercise 1: Emotion chart

Reread a book or rewatch a film you enjoy. As you do so, create a chart of character emotions. You can focus on the main character’s emotions or chart the emotions of multiple characters. Track the types of emotions experienced by the character(s), the size of the emotions, and what emotional clues are used.

Does a character experience or express large or small emotions differently? How do the biggest emotions line up with the biggest plot moments?

Exercise 2: Emotion reversal

Write about a small emotion you had in a large way—with several paragraphs and a layering of emotional clues. For example, spend a significant amount of time writing about mild irritation at no ripe avocados, a small amount of joy from getting the day’s Wordle, etc.

Now, write about a large emotion you had in a small way. This might be a phrase or a few sentences. You might dismiss the large emotion, compare it to something else and move on, etc.

Now, reflect. While often it’s useful to write about bigger emotions in a big way, and smaller emotions in a small way, in what circumstances would it be useful to do the reverse?

Exercise 3: Planning (or revising) a story

Plan out a novel that you intend to write. Which three scenes do you want to have the biggest, most explored emotions? How will the placement of these emotional scenes help the story? (You can also do this with a short story—however, choose one scene or moment to have the biggest, most explored emotions.)

If you are revising a story, find which scenes already have the biggest, most expressed emotions. Are these the scenes that should have the most emotional weight? Are they expressing or layering in the most effective way? As necessary, revise.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!