Big Mary Bennet Energy: 2022, A Year in Review

And now, as we reach the final day of 2022, it is time for my annual writing year in review.

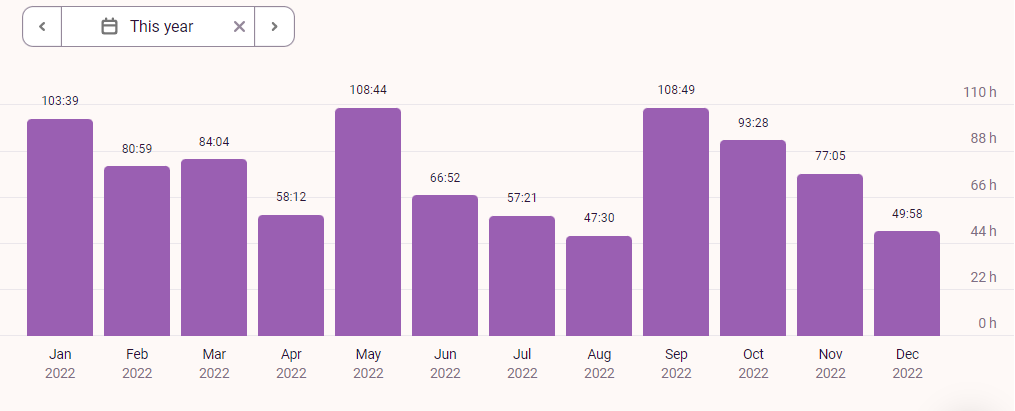

I spent 937 hours writing in 2022, and my year looks like a series of waves.

Due to a variety of outside factors, my writing time varied from 47 to 109 hours each month, but it did so in an aesthetically pleasing way, which is definitely a win.

(Note: 937 hours is less time than I spent writing in 2021, when I wrote for 1000 hours, but more than I spent writing in any previous year.)

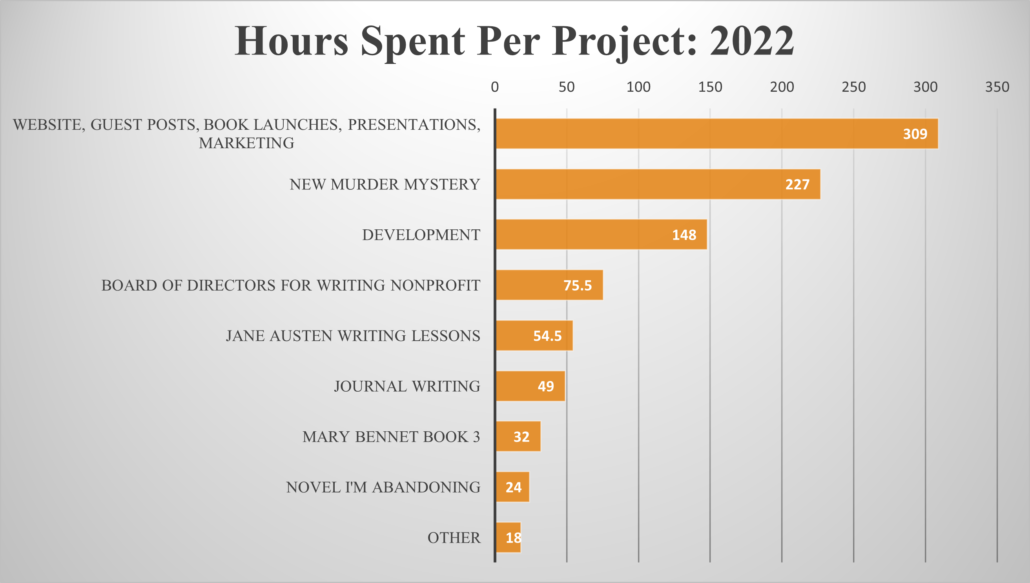

Which leads us to the next chart: how did I spend my time?

This year had big Mary Bennet energy, and that determined a lot of my writing hours. True, I only spent 32 hours doing final revisions on my third Mary Bennet novel. But the second and third books in the Mary Bennet spy series were both released:

The True Confessions of a London Spy in March 2022

The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception in September 2022

I had my launch party for The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception at This is a Bookstore/Bookbug in Kalamazoo, MI.

It was exciting to have these books released in close proximity, because then readers could enjoy the full story arc without having to wait very long. As you’d expect, two book releases takes up a lot of time, and I spent 309 hours on everything from my website to guest blog posts to presentations to marketing tasks.

This year was also thrilling for the first book in the series, The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet, which had several award wins and nominations:

-Winner of the LDSPMA Praiseworthy Award for Best Suspense/Mystery novel

-One of five nominees for the Mary Higgins Clark Award

At the Edgar Awards: me with three of the other finalists for the Mary Higgins Clark Award

-One of five finalists for the Whitney Award for Best Mystery/Suspense novel

The Big Question: Will we see more of Mary Bennet?

I have had so many readers finish the third book and ask, “Will we see more of Mary Bennet?” Others have asked if I will write a Kitty Bennet series.

The series was originally conceived as a trilogy. I wanted it to feel complete and have a satisfying resolution for Mary (and company) by the end of the third book.

However, there are other stories that I would love to tell about Mary and her sisters. So I think it’s fair to say that there will very likely be more books in Mary and/or Kitty’s futures.

That said, I have been working on this series non-stop from 2017 to 2022. Five full years. That’s a lot of time to spend in one story world, with one set of characters. A book takes me at least a year or two to write, and it’s very all-consuming. So I decided that the time had come to work on a brand new murder mystery.

The New Murder Mystery:

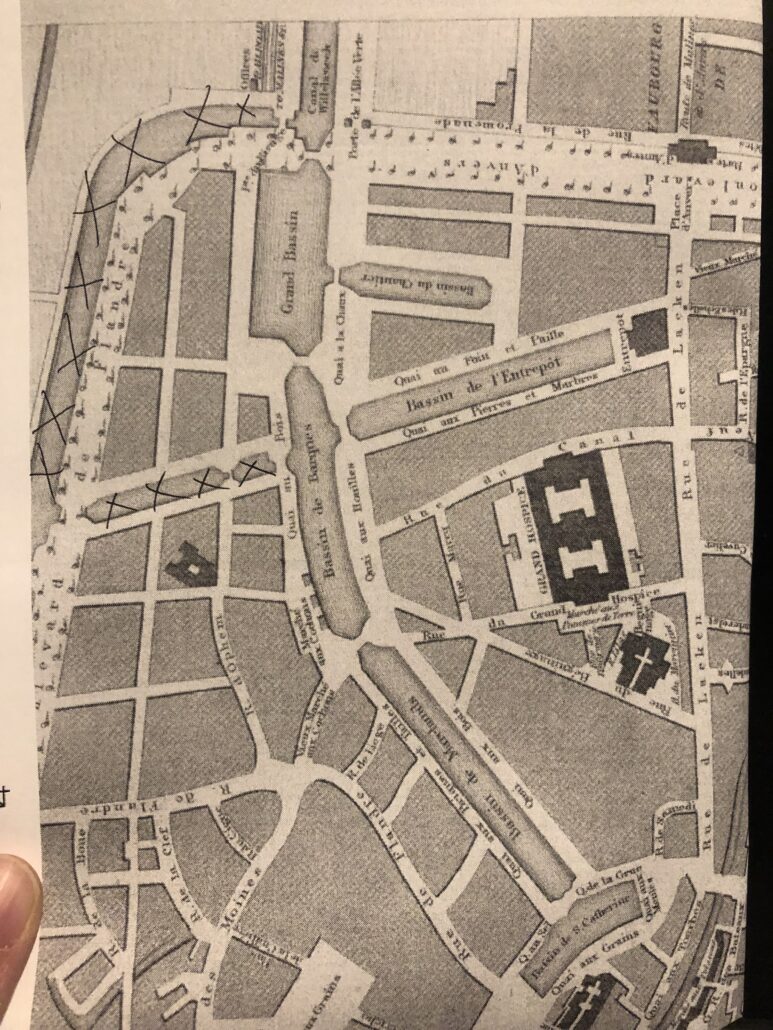

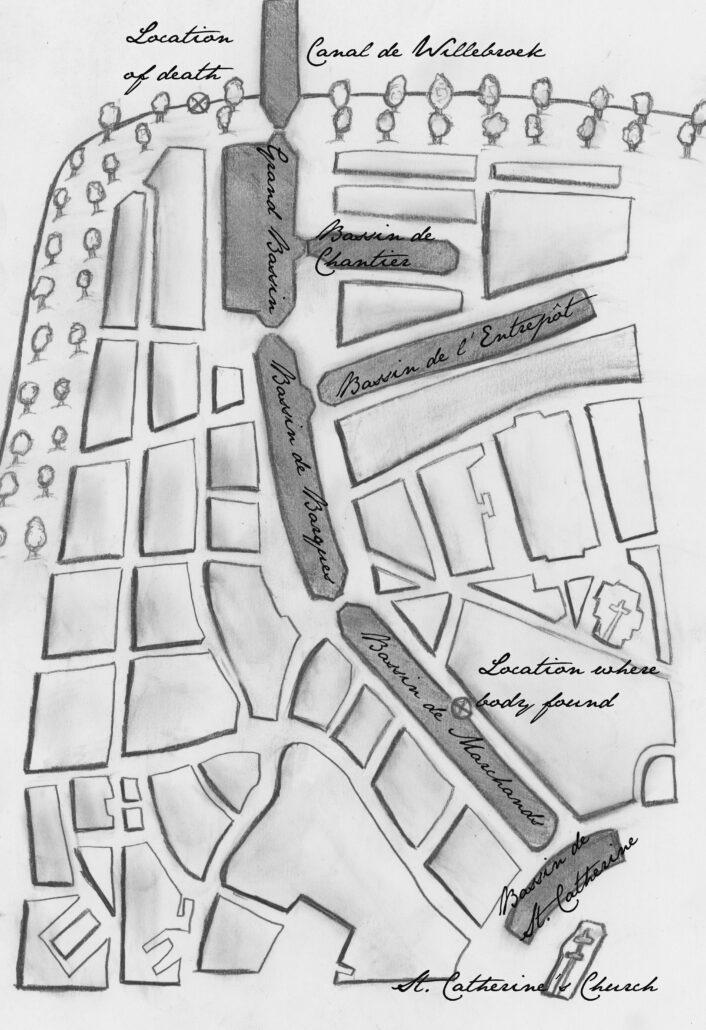

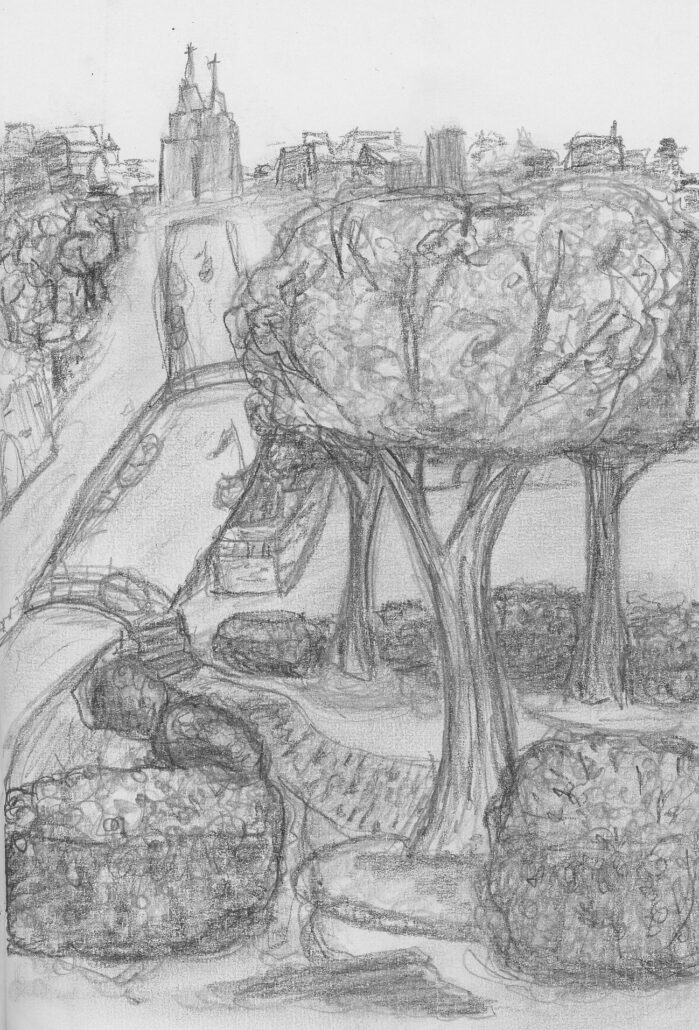

I’m still keeping this largely under wraps, but I will say that my new murder mystery is set in Paris in the late 1800s, with a number of fascinating historical figures. The main character of the book is a determined woman in her thirties trying to make her way in the world. But then there is a theft and a murder, and she is drawn into solving the mystery.

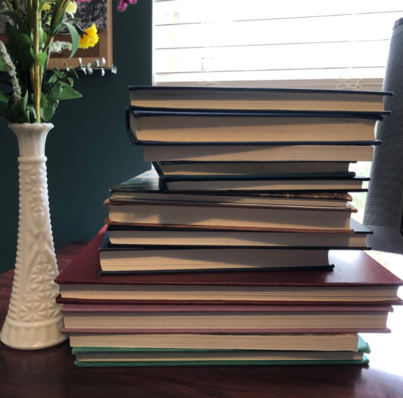

I spent 227 hours on this book in 2022. While I had to do a lot of research for the Mary Bennet novels, I already had a strong background on Jane Austen and Regency England. I did not have that same background for my new murder mystery, so I’ve had to do a lot of additional research on everything from politics to architecture. Fortunately, I love research. One thing I didn’t count towards writing time was studying French. I’m fluent in Portuguese, and reading Portuguese definitely helps with reading French, but knew I needed to study French itself to help me read some of the sources (including newspapers and a few biographies) that are only available in French.

A few of the research books I’ve read for my current novel

While I love research, one cannot research forever. One of the things that I am most happy about for this year is that I found my main character’s voice, I found my narrator voice, and I found the voices of many of my other characters.

I’m now at the 60% mark on the first draft. In the new year, I plan to finish the first draft and then revise, revise, revise.

What Else Counted as Writing:

There are endless other things that counted as writing this year, but here’s a few of note:

-Choosing out formal gowns. I rented dresses for both the Edgar Awards and the Whitney Awards, and I definitely counted the dress search as writing time. (Under my Development category, which includes all writing and career development.)

My dress for the Whitney Awards. Both my dress for the Edgars and the Whitneys were from Rent the Runway.

-I ran a successful Kickstarter for a writing nonprofit and helped publish an anthology.

-I abandoned a novel. I went back and began another revision on an old mystery novel I wrote in the mid-2010s. And then I decided it’s not the right book, so I am officially abandoning it. We’re all better off.

-I wrote 17 new Jane Austen Writing Lessons, focusing on what Jane Austen can teach us about writing dialogue and writing emotions.

-I worked on a few short stories. And I had two short stories published, both with a bit of a religious bent: “The Gift of Undoing” in Saints, Spells, and Spaceships, and the darkest story I’ve ever written, “Burdens,” in Irreantum.

My Writing Plans for 2023:

I have a number of goals, including setting up bookstore and library visits (note: if you’re a bookseller or librarian, I am available for both in-person and virtual visits).

Mostly though, I’m going to buckle down and write, so you can read more of my short stories and novels in the future.