#19: Make Your Characters Sympathetic

In a letter to her niece Fanny Knight in March 1817, Jane Austen mentioned that she had a new novel, nearing readiness for publication: “You will not like it, so you need not be impatient. You may perhaps like the Heroine, as she is almost too good for me.”

Jane Austen died a few months after her letter, but her family had the novel published posthumously. That novel is Persuasion, and its heroine, Anne Elliot, is—despite Austen’s self-deprecating comments—a true gift to readers.

Anne Elliot is a prime example of a sympathetic character. She broke off an engagement with Captain Wentworth ten years before the start of the novel, and now he is back in her life. She wonders—and we wonder, with just as much desperation and longing—if she will have a second chance with him.

A sympathetic character is a character who we feel compassion for and connection to. It is a character that we find likeable.

The Oxford English Dictionary (also known as the OED) is over 21,000 pages long and is probably the most massive English dictionary in the world. It is also my favorite dictionary (yes, I have a favorite dictionary). Note: I don’t own a physical copy—that would be insane, but it is online and accessible through many library subscriptions!

Image of the Compact OED from Aalfons. The normal version is almost two dozen huge books.

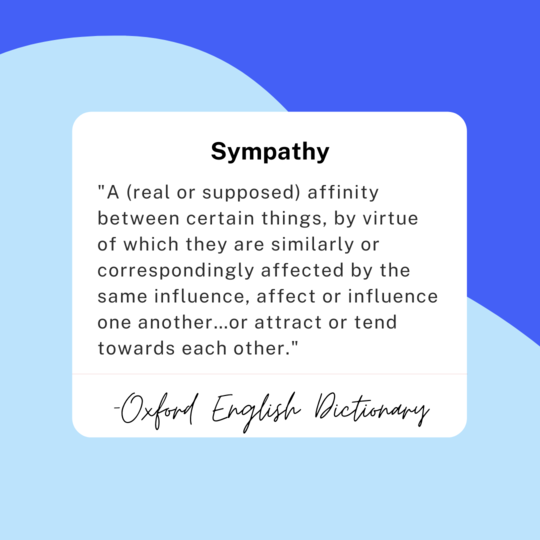

The OED goes into great depth in defining the word sympathy. We’ll look at some of the OED’s definitions of sympathy, and then use examples from Persuasion to examine how to use these definitions to create sympathetic characters.

The OED cites an example from 1601 which talks about the sympathy between iron and loadstone—in other words, sympathy is like a magnet and a paperclip: there is some inherent similar quality which creates an attraction between them.

One of the main reasons we turn to literature is because stories create feelings of sympathy. We see ourselves in literature. Stories changes us. We become part of the experience in the text, and the text becomes part of our own experience.

In the latter half of Persuasion, Anne is living in Bath with her father and sister. She attends a concert with them, and Captain Wentworth is present. Anne and Wentworth have a nice conversation before the concert, but during the concert Anne is seated next to another man who is interested in her, Mr. Elliot. We see ourselves in Anne as, during the concert, she tries to catch Wentworth’s eye, but is unable to. We feel Anne’s frustrations with Mr. Elliot and his flirtation; like her, we cannot truly be interested in him. We are one with Anne and agree with her motives and her actions when she manages to change seats partway through the concert so she is at the edge of a row and has the hope of talking to Wentworth.

Captain Wentworth leaves before the concert is over:

He must wish her good night. He was going—he should get home as fast as he could.

“Is not this song worth staying for?” said Anne, suddenly struck by an idea which made her yet more anxious to be encouraging.

“No!” he replied impressively, “there is nothing worth my staying for;” and he was gone directly.

Jealousy of Mr. Elliot! It was the only intelligible motive. Captain Wentworth jealous of her affection! Could she have believed it a week ago—three hours ago! For a moment the gratification was exquisite. But alas! There were very different thoughts to succeed. How was such jealousy to be quieted? How was the truth to reach him? How, in all the peculiar disadvantages of their respective situations, would he ever learn her real sentiments? It was misery to think of Mr. Elliot’s attentions. – Their evil was incalculable.

Anne is an especially sympathetic character in this scene.

A character is sympathetic when we as readers can:

- Understand the character’s perspective

- This scene is in Anne’s point of view, and with Austen’s presentation, it is easy to understand Anne’s perspective on the situation, her history with Wentworth, and her desires. We are aided by internal thought as the narration slips into Anne’s mind and thoughts.

- This scene also helps us understand Wentworth’s perspective. He is not the point of view character, but his perspective is revealed through his dialogue and behavior, and we can understand him as a person and feel a shared humanity with him.

AND/OR

- Relate to the character’s motives and actions

- In this scene, we can relate to Anne’s motives, particularly her desire to fix things between her and Wentworth.

- Her actions are also actions that we feel like we would take if we were in the same situation.

Note that there are plenty of times when we might not relate to the character’s motives and actions—personally, I do not relate to Anne’s actions as much during the first half of the novel, when Anne avoids attempting to have an in-depth conversation with Captain Wentworth. But even if I don’t agree with her actions (or in other cases, her motives) I can understand why she’s making her choices, so I can still maintain a level of sympathy for her.

Additional techniques for creating sympathetic characters

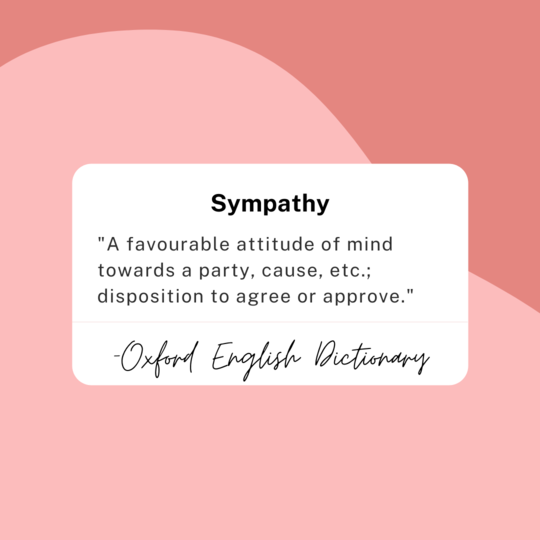

Now we’re going to look at three more definitions of sympathy from the OED, which will help us understand additional techniques and approaches which can be used to create sympathetic characters.

In the screenwriting book Save the Cat, Blake Snyder talks about the need for the audience to feel sympathy for the main character early on. He calls this the “save the cat” moment; in some films, the main character will literally save a cat, and this will instantly endear them to us. Basically, we feel favorably when people take actions that we can agree or approve of, and in general, as people, we approve of acts of kindness, we approve of someone doing something good or self-sacrificing. We like kind people.

Near the beginning of Persuasion, Anne has a strong “save the cat” moment. Anne’s nephew is ill, and this will prevent her sister from going to eat dinner at another family’s house. Anne’s sister very vocally and desperately expresses her desire to attend the dinner—she suffers from what today we like to call FOMO, fear of missing out. Anne has even better desires than her sister for attending the dinner—Captain Wentworth will be there, and Anne has not seen him in the ten years since she broke off their engagement.

Anne makes the decision to take care of her nephew so that her sister and brother-in-law can go to the dinner:

She knew herself to be of the first utility to the child; and what was it to her, if Frederick Wentworth were only half a mile distant, making himself agreeable to others!

Having a save the cat moment can help us sympathize with not just with a main character, but with any character. If, for example, you want us to have sympathy and understanding for an antagonist’s motives (which can be a powerful tool to make them a rounded, full character), have them do something good or kind for another character.

I talked about this in the post on passive characters—we sympathize with Fanny Price in Mansfield Park because of the poor way others treat her. We sympathize with suffering (though if there is too much suffering or a character feels pitiable, sometimes we find it too hard or uncomfortable to sympathize).

We also like to root for underdogs, for people who have to prove themselves. Anne Elliot is undervalued by her father and sisters; in the opening scenes of the novel, they dismiss her ideas and advice. We also see Anne suffering when Wentworth pursues another woman, and we feel for Anne in these moments.

Conformity is about norms, and we sympathize with characters within certain norms. We sympathize with characters that meet our expectations of behavior and temperament. In literature, characters are often better than ourselves: they are a little more consistent, a little more understandable. They can be better examples of certain virtues or ideologies.

Yet if characters are too good or too perfect or too smart or too capable, we stop sympathizing with them. Just as in real life, we often don’t like people who seem too perfect; we feel more distance between us and characters that seem so much greater or better than us, because they are not like us.

Sympathetic characters must be like us: they must have weaknesses. They must try and they must fail, repeatedly, because it is trying and failing and trying again that makes us human.

Anne’s weaknesses are plenty: she is at times too easily persuadable. She veils her emotions. She does not stand up for herself. And because of this, she feels real and we sympathize with her struggles and failures and attempts to achieve her goals.

The Spectrum Between Sympathetic and Unsympathetic Characters

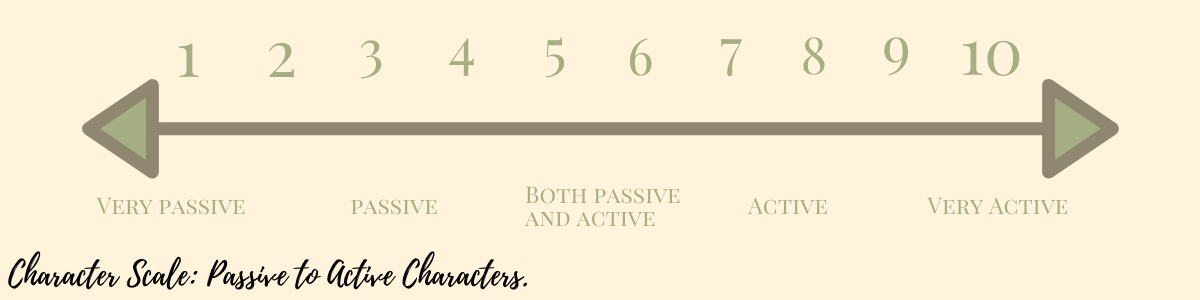

Like with active and passive characters, there is a spectrum between sympathetic and unsympathetic characters, and characters typically move up and down this spectrum over the course of a story. At times characters—even make characters—are predominantly unsympathetic. Next week I’ll focus on effectively using unsympathetic characters.

Whether your character is mostly sympathetic or only occasionally sympathetic, it helps the reader connect to the story. We like spending time with people we like, with people we have sympathy for. We root for them. And we are excited to travel with them on their journeys.

Exercise 1: There is a great Writing Excuses podcast episode on sympathetic characters (which I encourage you to listen to!). In addition to some of the points covered in this writing lesson, they address several other techniques that can help create sympathy for characters:

- Character self-awareness

- Humor

- Vulnerability and openness

Take a character from a book or film that you find sympathetic, and examine what specifically makes them sympathetic, whether it’s the point of view, suffering, backstory, imperfections, relatable motives, humor, or other principles entirely.

Exercise 2: Write a brief scene of a character doing something that we generally find unsympathetic (i.e. taking a toy from a young child, ripping up a student’s paper, etc.). Write this scene in a way that will make a reader feel sympathy for this character.

Exercise 3: Take one of your characters that is generally sympathetic and write a brief scene that makes them less sympathetic. Then, take one of your characters that is generally unsympathetic and write a brief scene that makes the more sympathetic. What did this achieve? What would the impact of this scene be on an audience? Does this scene teach you anything about your own characters?