#43: Use Discovery to Create Satisfying Resolutions and Denouements

If an airplane pilot crashes the plane while landing, it doesn’t matter how good the rest of the ride was. The same goes for novels—if you don’t land the ending, the book will not be satisfying.

Jane Austen is a novelist who always “lands the ending.” One of the main ways she does this is by incorporating discoveries into the resolution of the story: in particular, she uses discoveries to answer the big questions that have been raised throughout the story.

In lesson 40, we talked about some of the big questions raised in the novel Persuasion, including:

- What will Anne’s future look like?

- Can Anne and Wentworth reconcile?

Most of the other big questions in the book have been explored and answered by the time we hit the last two chapters of the novel, but not these two questions. Characters and readers have yet to discover the resolution.

The second to last chapter of Persuasion acts as the final “unravelling,” the final section of the climax sequence where the most important questions must be answer, the most important discoveries made. In this chapter, Anne and Captain Harville discuss love and the inconstancies of men and women—who suffers the most from loss of love? Whose feelings are the most tender, the most constant? Captain Wentworth overhears their conversation, and as a result of Anne’s words, writes her a letter which begins:

I can listen no longer in silence. I must speak to you by such means as are within my reach. You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope. Tell me not that I am too late, that such precious feelings are gone for ever. I offer myself to you again with a heart even more your own, than when you almost broke it eight years and a half ago. Dare not say that man forgets sooner than a woman, that his love has an earlier death. I have loved none but you.

Upon reading the letter, Anne cannot sit still—she goes out into Bath, and when she sees Captain Wentworth, she joins him on a walk. And here, here we discover the answers we’ve been seeking. Anne and Captain Wentworth do reconcile, they express their love to each other, and they become engaged.

In a novel, when questions are raised for the characters, readers want answers by the end of the story. Some of these discoveries occur, and should occur, throughout the book, but some should be saved for the end.

Answering a key question or key questions near the end of the novel provides a satisfying resolution for both the characters and the reader.

In Persuasion the key discoveries are made in the second to last chapter. But there are still more discoveries saved for the denouement.

Discoveries in the Denouement

The denouement serves to show what happens as a result of the final resolution. It is a chance for characters to make any final smaller discoveries, to show any relationship changes, and to wrap up any lingering subplots which have not been resolved.

In the novel Persuasion, the final chapter serves as the denouement. It begins with the following paragraph, which reassures us that the key questions will truly be resolved in the way in which we as readers hope:

Who can be in doubt of what followed? When any two young people take it into their heads to marry, they are pretty sure by perseverance to carry their point, be they ever so poor, or ever so imprudent, or ever so little likely to be necessary to each other’s ultimate comfort. This may be bad morality to conclude with, but I believe it to be truth; and if such parties succeed, how should a Captain Wentworth and an Anne Elliot, with the advantage of maturity of mind, consciousness of right, and one independent fortune between them, fail of bearing down every opposition?

There are a number of other minor discoveries in the final chapter as part of the denouement:

- We discover Sir Walter’s view on his daughter’s engagement. He approves (he decides that Captain Wentworth has a nice balance of physical attractiveness and fortune, which are two of the only things that matter to him).

- We discover that Anne’s sister Mary is happy for her, and (mostly) not jealous.

- We discover how Anne’s other suitor, Mr. Elliot reacts:

The news of his cousin Anne’s engagement burst on Mr. Elliot most unexpectedly. It deranged his best plan of domestic happiness, his best hope of keeping Sir Walter single by the watchfulness which a son-in-law’s rights would have given.

- We discover that Mrs. Clay has become Mr. Elliot’s mistress (and thus, Anne’s father Sir Walter is safe from Mrs. Clay’s scheming).

- We discover that Lady Russell and Captain Wentworth are able to reconcile with each other. This is an important discover, as Lady Russell was the person who convinced Anne to break off her original engagement to Wentworth eight years before.

- We discover the resolution to the subplot of Anne’s friend Mrs. Smith being in poverty: Captain Wentworth is able to use his connections to secure Mrs. Smith’s fortunes, her health improves, and she maintains a good friendship with Anne.

Austen, of course, never leaves her endings completely tidy—there’s never a sense of complete assured happiness. In the final paragraph, we read:

Anne was tenderness itself, and she had the full worth of it in Captain Wentworth’s affection. His profession was all that could ever make her friends wish that tenderness less; the dread of a future war all that could dim her sunshine. She gloried in being a sailor’s wife, but she must pay the tax of quick alarm…

Austen makes no pretense that Anne and Wentworth’s lives will be perfect. But it is a wonderful resolution because it answers the core, larger questions of the book. It’s a wonderful resolution because this discovery is made in a beautiful way. And it’s a wonderful resolution because the denouement is able to provide the reader with discoveries for lingering questions and subplots.

A Recap

We’ve spent the past seven lessons talking about discovery. To recap, we covered:

- Why you should give your characters things to discover

- How to establish an information gap or start a character on the journey toward discovery

- How to create a progression of knowledge discovery

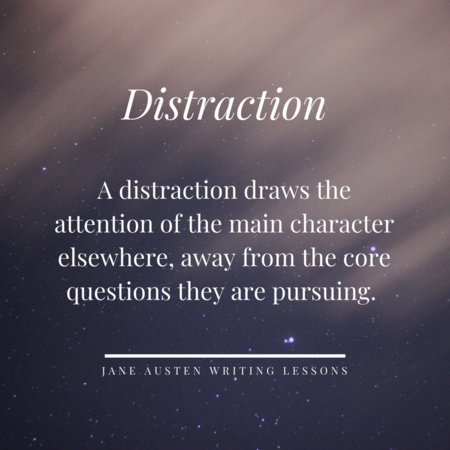

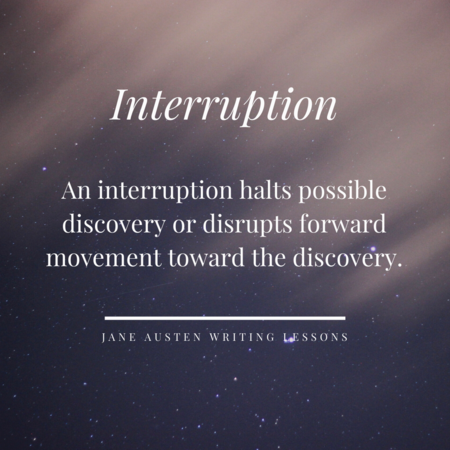

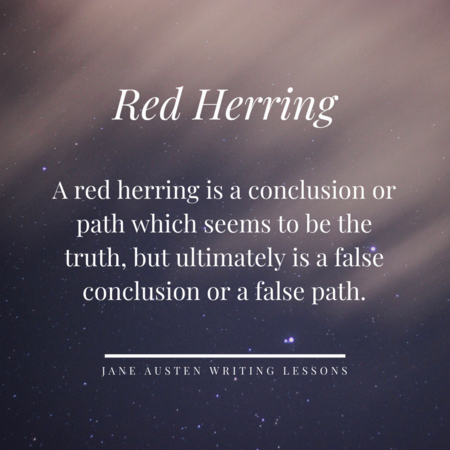

- How to use distractions, interruptions, and red herrings

- How to use foreshadowing

- How to use large discoveries and plot twists

- Using discovery in the resolution and denouement (this lesson)

Discovery is a powerful tool that can be used in any sort of fiction to drive the character forward and invoke the reader’s interest. Ultimately, the process of discovery assists the character on their external journey, as they interact with the world and find their place in it. Discovery is also fundamental to a character’s internal journey: it gives them reason to change, and sometimes the greatest discoveries come from reflection about themselves, as characters recognize who they really are.

Exercise 1: Write a new denouement

Take a short story or a novel that you have written and write a new denouement. Keep the main resolution the same, but write a different denouement, which resolves subplots, relationships, and other small discoveries in a new way.

Exercise 2: Write just the ending of a story

The author Victoria Schwab (also published as V.E. Schwab) writes her climax and denouement first, before writing anything else. In episode 15.42 of Writing Excuses she explained, “I don’t do anything until I’ve planned the ending. The ending…and that climax through the last page determines the entire story I’m telling….Rather than write toward the end, and think ‘What kind of resolution do I need in order to fulfill the promises I’ve made early on?’, I write backwards, from the end, and make those promises from the ending that I know I want to achieve.”

Take a story idea that you haven’t used and write the ending. To reemphasize—you are just writing the ending of the story, not the beginning or the middle. Consider what sorts of discoveries would you like your characters to make at the end of the story, and what emotions you would like to evoke in your reader. Also, ask yourself the same question that Victoria Schwab asks herself: “Who are my characters the moment we leave them?”

Once you’ve written the ending, consider what storytelling it will take to reach this ending, and how to get your characters to this point.

Exercise 3: Best and Worst Endings

Think of two stories, one which had a satisfying and rewarding ending, and another which had an ending that didn’t quite work for you. Now go back and analyze the endings—what specifically made the endings effective and ineffective for you as a reader?