In the passage between Mr. Darcy and Mr. Bingley, there were two paragraphs of dialogue that did not include any dialogue tags or action beats. The paragraph that begins “I certainly shall not” is Mr. Darcy’s dialogue, while the paragraph that begins “Oh! she is the most beautiful creature I ever beheld!” is Mr. Bingley’s.

Omitting a dialogue tag focuses the reader on what the characters are saying, and it increases the pace by which we read the dialogue. In Austen’s novels, dialogue tags are used only if they are necessary for comprehension, if they will positively impact the rhythm or cadence, or if they truly add something to the reader’s understanding of the characters and their conversation. The rest of the time, she does not include dialogue tags.

In Elliott Slaughter’s study on dialogue tags in Pride and Prejudice, he found that for 51% of the dialogue, Austen does not use a dialogue tag or any sort of attribution. This is especially common during conversations between two characters. In some passages, the identity of the speakers will be made clear once, either at the start of the conversation or in the actions before the conversation, and then Austen will give five, six, or ten lines of dialogue without any tags or attributions. While it’s easiest to omit dialogue tags if there are only two characters, Austen often omits tags in conversations with larger groups of characters.

In a later scene in Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Darcy’s makes a declaration on Mr. Bingley’s tractability, and then we read:

“You have only proved by this,” cried Elizabeth, “that Mr. Bingley did not do justice to his own disposition. You have shown him off now much more than he did himself.”

“I am exceedingly gratified,” said Bingley, “by your converting what my friend says into a compliment on the sweetness of my temper. But I am afraid you are giving it a turn which that gentleman did by no means intend; for he would certainly think the better of me, if under such a circumstance I were to give a flat denial, and ride off as fast as I could.”

“Would Mr. Darcy then consider the rashness of your original intention as atoned for by your obstinacy in adhering to it?”

“Upon my word, I cannot exactly explain the matter, Darcy must speak for himself.”

“You expect me to account for opinions which you choose to call mine, but which I have never acknowledged. Allowing the case, however, to stand according to your representation, you must remember, Miss Bennet, that the friend who is supposed to desire his return to the house, and the delay of his plan, has merely desired it, asked it without offering one argument in favour of its propriety.”

“To yield readily—easily—to the persuasion of a friend is no merit with you.”

“To yield without conviction is no compliment to the understanding of either.”

The first two paragraphs include dialogue tags, for Elizabeth and Mr. Bingley, but then the rest of this dialogue we can assume by context that the lines belong to Elizabeth, Mr. Bingley, Mr. Darcy, Elizabeth, and then Mr. Darcy. Descriptions of how these characters are speaking is not necessary—we know them and can make assumptions on their tone and mannerisms based solely on what they say.

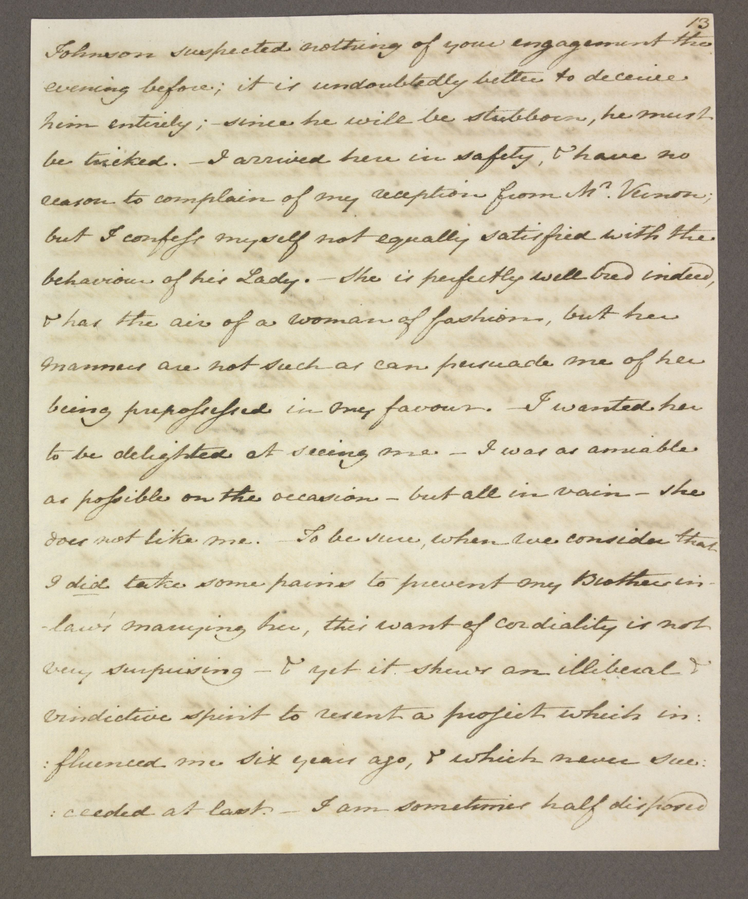

There are a few places in Pride and Prejudice where the speaker is unclear, which has led to rather exciting scholarly debates. In a letter about Pride and Prejudice which Jane Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra, she said,

There are a few typical errors; and a “said he,” or a “said she,” would sometimes make the dialogue more immediately clear; but “I do not write for such dull elves” as have not a great deal of ingenuity themselves.

While Austen wished she had added a few more uses of “said he” and “said she,” the fact is that there are 633 lines of dialogue in Pride and Prejudice which do not include dialogue tags, and, with a few possible exceptions, they are not necessary in these passages. As you consider what sorts of dialogue tags you want to use in your own writing, consider also when to use dialogue tags, and when to omit them.

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/68-Square.png

1080

1080

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Katherine-Cowley-Logo-2-1030x589.png

Katherine Cowley2023-09-29 08:47:492023-09-29 08:47:51#68: Establishing Relationships and Character Connections in Fiction

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/68-Square.png

1080

1080

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Katherine-Cowley-Logo-2-1030x589.png

Katherine Cowley2023-09-29 08:47:492023-09-29 08:47:51#68: Establishing Relationships and Character Connections in Fiction https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/68-Square.png

1080

1080

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Katherine-Cowley-Logo-2-1030x589.png

Katherine Cowley2023-09-29 08:47:492023-09-29 08:47:51#68: Establishing Relationships and Character Connections in Fiction

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/68-Square.png

1080

1080

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Katherine-Cowley-Logo-2-1030x589.png

Katherine Cowley2023-09-29 08:47:492023-09-29 08:47:51#68: Establishing Relationships and Character Connections in Fiction