Review of Netflix’s Persuasion (with Survey Data)

I love adaptations, and I love Jane Austen. So I had to watch Netflix’s new adaptation of Persuasion, starring Dakota Johnson, Cosmo Jarvis, and Henry Golding. I decided to make a movie night of it and invited a bunch of friends over. We watched the film. There was much laughter. The credits rolled. And then I handed out surveys.

Yes, surveys.

You come to a girls night at my house, and you may end up taking a survey.

What was most interesting to me was actually the qualitative results–what people liked and disliked from a film standpoint–but first, let’s look at overall impressions.

Overall Impressions/Quantitative Results: Enjoyment Factor

I minored in film in college, and I did a masters in English. I love movies, and I love books. And I feel like they’re very different things. But in terms of a movie that’s worth watching, you need to know if it’s enjoyable or not. That’s a fundamental part of the film viewing experience.

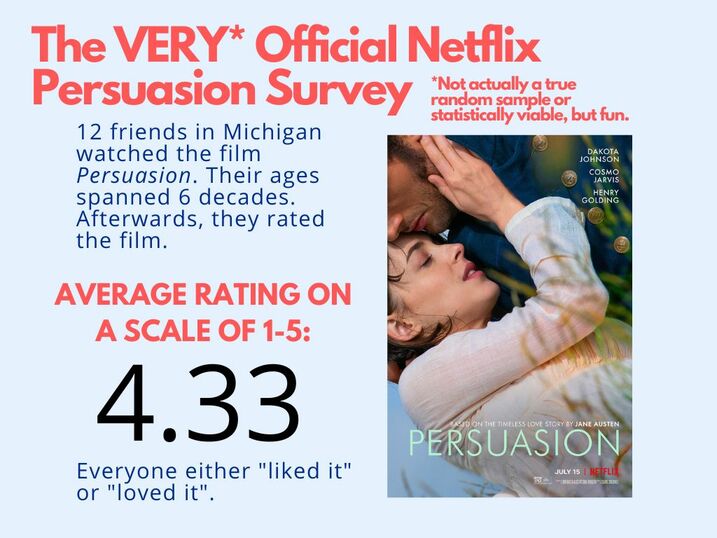

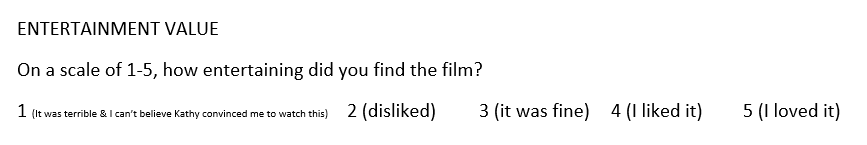

I gave everyone a scale of 1 to 5 and asked them how much they enjoyed the film.

And as you saw from the first graphic in this post, people liked the movie. We had an average of 4.33 stars. And everyone either liked it or loved it.

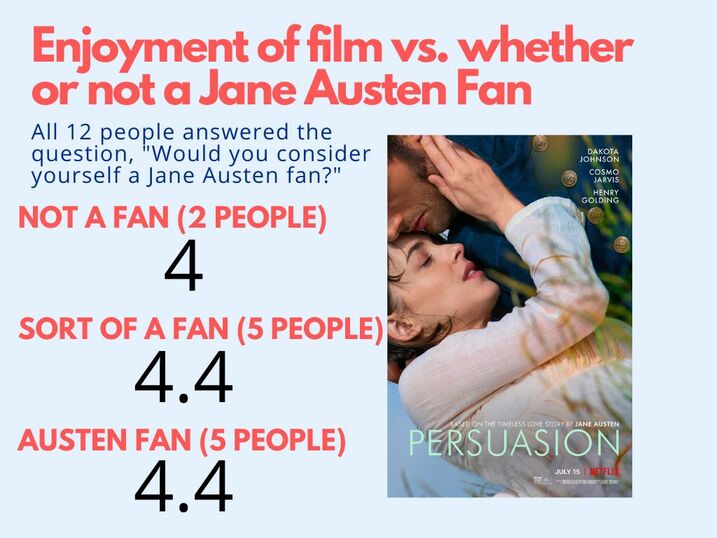

I also wanted to see whether or not someone’s enjoyment of the film was influenced by how much they feel like a Jane Austen fan. Now, there is no official rubric for what makes someone a true Jane Austen fan (though a rather hilarious character in the film Austenland attempts to define a true fan). So I simply let people judge for themselves.

Would you consider yourself a Jane Austen fan?

- Yes

- No

- Sort of

Note that I included a “sort of” category. To me, I see people who rated themselves as “sort of” Jane Austen fans as casual fans or those who might have engaged with mostly 1 or 2 of her books. But I didn’t put a description–I wanted people to put themselves wherever they felt most comfortable.

And here’s the results, with the averages of how they rated the film:

In general, those that either consider themselves Jane Austen fans, or “sort of” Jane Austen fans, rated the movie higher than those who didn’t.

One lady loves Jane Austen, and Persuasion is her favorite novel. She has watched (and owns) other adaptations. And she gave the film 5 stars.

The Qualitative Results: Filmic Choices

Then came the qualitative questions. I asked what, from a film technique standpoint, people thought worked well, and what didn’t work as well for them.

Survey Results: What Worked Well in Netflix’s Persuasion

There was a wide range of responses. One person, a self-professed Jane Austen fan, wrote:

“I felt like the breaking of the fourth wall was a wink and a nod to the humor of the author herself.”

Several other people also commented on how they liked the breaking the fourth wall and Anne’s direct dialogue with the camera/viewer.

The cliffs scene was a favorite, someone else really liked the dialogue, and people generally liked the emotions that were conveyed:

“I thought it captured well [the] regret, sorrow, and second chances.”

There were people who mentioned really liking:

- The music

- The costumes

- The dialogue

- That the storyline was clear

- Mary’s character/the humor she added to the story

One person, a Jane Austen fan, wrote:

“The Elliots were all true to Austen’s characters.”

I felt the same. Mary, Elizabeth, Sir Walter, the Musgroves–they managed to capture some of the essence of Austen’s characters.

One person who was not a Jane Austen fan wrote:

“I liked that I could understand it all. Older English mixed with modern. Some other movies I get lost sometimes cause of the language.”

For her, the modern references and metaphors (“I can never trust a 10”) really helped make the film more accessible.

I’ll close with one last positive comment:

“I loved all of it.”

Survey Results: What Didn’t Work a Well in Netflix’s Persuasion

First, I went to film school. What “doesn’t work” is a very subjective thing. And it’s almost more useful to consider what the goals of the film were and how well it achieved those goals.

However, I decided to spare my guests a 30-minute lecture on how to judge a film’s merit, and instead just asked on the survey “What didn’t work as well for you?”

Here were a few of the responses:

“I thought Anne drank too much.”

This is a definite shift to a book. Anne may or may not be an alcoholic in the movie.

Another person comment on the modern references:

“The modern language/references were occasionally jarring against the 1800s visuals.”

This is interesting because I only had two people comment on the modern languages/references. One person positively, and one person semi-negatively.

I’m someone who loves historical things. I put hundreds of hours into making my Jane Austen-inspired novels historically accurate, and I tried to make the language match Austen’s. But I thought this film was cohesive in being a bit ahistoric–not completely accurate costumes, some modern languages and references, the very uncomfortable octopus sucking scene, the frowny face drawn by Mary on her forlorn note. So even though it’s not how I’ve approached my own Austen adaptations, the modern languages/references worked.

Most people didn’t have any complaints. I got a lot of no responses on this final question, and several that read:

“No major criticisms.”

And

“Nothing, it was fun.”

Some Positive Results

One person commented on her survey:

“Now I want to read it.”

There were several other people who verbally expressed the same sentiment. And if a film makes you want to read Jane Austen, I always see that as a good thing.

Several other people (including people who had given the film a “4: I liked it”) plan to rewatch it, some of them with their husbands.

My Own Personal Thoughts

I thoroughly enjoyed myself.

I love the original novel. I love Jane Austen’s use of language. I love the nuance. I love the friendship with Mrs. Smith and that entire subplot (which was not included in the film). I like Jane Austen’s subtle commentaries on the war, on politics, on rhetoric, on education, on the role of the social sphere in a woman’s life. And these are all good, beautiful things that were not in the film.

But I thought it was a really good adaptation.

Fresh? Yes.

Interpreting characters a little differently? For sure.

Taking a new vision to Austen? Yes.

I think it’s useful to note that the director, Carrie Cracknell, is largely a theatre director. I feel like theatre-goers expect a wider range of adaptations than film-viewers, and so this adaptation may surprise some viewers. But generally, I think people will enjoy it.

Hardcore Jane Austen fandom does have a solid contingent of purists that can be rather judgmental on anything that does not fit their conceptions of what a Jane Austen adaptation should look like. If you’re looking for complete accuracy for the novel, you’re going to be disappointed. However, that’s not what makes an adaptation interesting to me.

There’s a great film theory article by Richard Stam called “Beyond Fidelity: The Dialogics of Adaptation.” He talks about how “fidelity” and the moral language we use to judge film adaptations can actually get in our way as film viewers. He posits that a film may be choosing an essence of the original and putting that into a new genre. But an adaptation is not pure transference–Stam talks about how an adaptation can be:

- Translation

- Reading

- Dialogization

- Cannibalization

- Transmutation

- Transfiguration

- Signifying

He spends a great number of pages going into each of these things–so if you want to read about how an adaptation can be a dialogue with the original, or a transmutation, check out his article.

(I do want to point out that there have also been some very racist critiques of Persuasion. Which is honestly very sad to me. I personally think color blind cast is amazing. Also, despite the white-ness of many Austen adaptations, Regency England was actually quite a diverse place, and that were people of many races at all levels of society.)

Netflix’s Persuasion is a film that I plan to rewatch. Despite loving the novel Persuasion, I’ve never actually seen the other film adaptations, and now I’m interested in watching them–broadening my horizons and such.

Now Go Forth and Watch!

Despite my survey being so VERY official (and not statistically significant), I think it’s fair to recommend that you go watch Netflix’s Persuasion and judge the film for yourself.