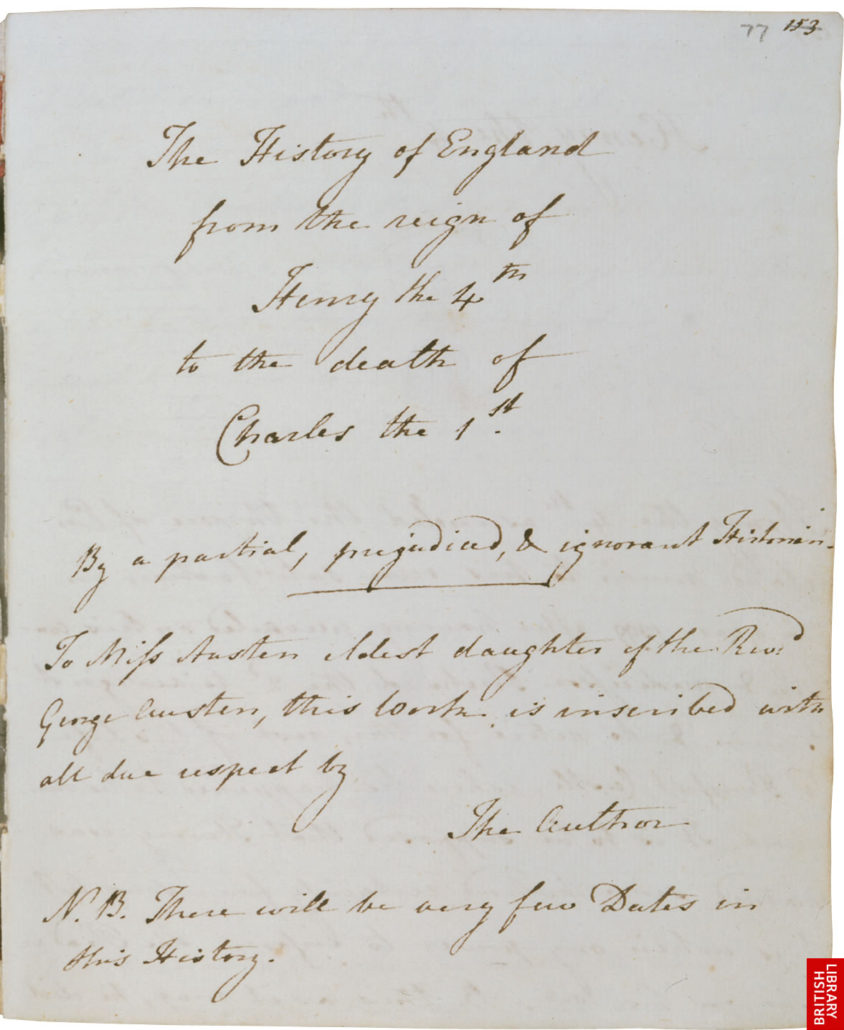

Another handwritten page by Jane Austen, from The British Library.

Jane Austen continues to establish the reader-writer contract in the first paragraph:

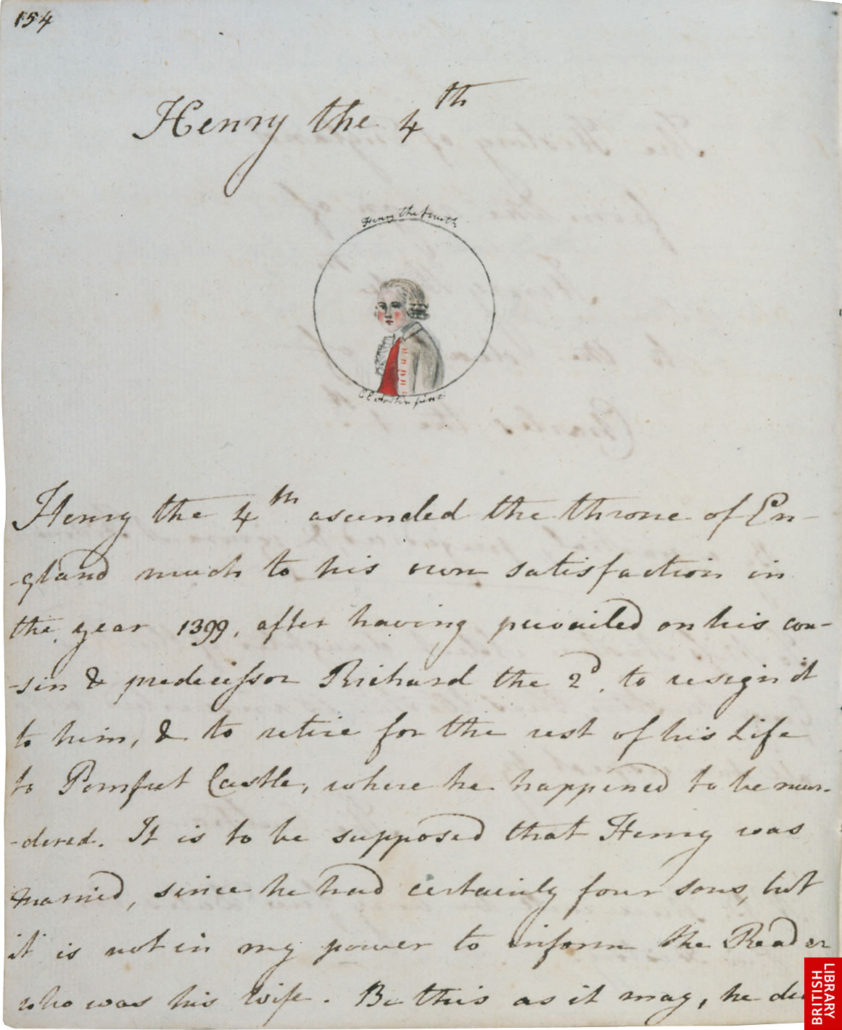

Henry the 4th ascended the throne of England much to his own satisfaction in the year 1399, after having prevailed on his cousin & predecessor Richard the 2d to resign it to him, & to retire for the rest of his Life to Pomfret Castle, where he happened to be murdered. It is to be supposed that Henry was married, since he had certainly four sons, but it is not in my power to inform the Reader who was his wife. Be this as it may, he did not live for ever, but falling ill, his son the Prince of Wales came and took away the crown; whereupon, the King made a long speech, for which I must refer the Reader to Shakespeare’s Plays, & the Prince made a still longer. Things being thus settled between them the King died, & was succeeded by his son Henry who had previously beat Sir William Gascoigne.

This firmly establishes the point of view of the speaker, her (intentionally) biased relationship with the subject matter, and the humor created as a result.

Promises Made and Kept

Swiftly, in the beginning of the piece, our expectations have been set, and the reader-writer contract has been forged. Here are a few of the promises that have been made:

- Genre: Parody/satire, with the effect of creating humor and commentary, both on these figures in history, and on the persona of a historian

- Plot: marriages, deaths, killings, and random details about a series of rulers from Henry the 4th to Charles the 1st.

- Character: the characters of the past are set forth, but the narrator herself seems to be a character

- Style: playful, amusing

- Point of view: first person, ignorant “historian” (not simply a reader, but someone making a claim that despite their ignorance, they still deserve the title “historian”)

These promises, having been made at the start, are kept and built upon throughout the piece.

A few of my favorite lines demonstrate this quite well:

“This unfortunate Prince lived so little a while that nobody had time to draw his picture.”

“Tho’ inferior to her lovely Cousin the Queen of Scots, [she] was yet an amiable young woman & famous for reading Greek while other people were hunting.”

“He was beheaded, of which he might with reason have been proud, had he known that such was the death of Mary Queen of Scotland; but as it was impossible that he should be conscious of what had never happened, it does not appear that he felt particularly delighted with the manner of it.”

The Satisfying Conclusion relies on these initial promises

In order for the conclusion of a story to be satisfying, it must fulfill the promises that it has made.

The following is the final paragraph of Jane Austen’s “History”:

The Events of this Monarch’s reign are too numerous for my pen, and indeed the recital of any Events (except what I make myself) is uninteresting to me; my principal reason for undertaking the History of England being to prove the innocence of the Queen of Scotland, which I flatter myself with having effectually done, and to abuse Elizabeth, tho’ I am rather fearful of having fallen short in the latter part of my Scheme. —. As therefore it is not my intention to give any particular account of the distresses into which this King was involved through the misconduct & Cruelty of his Parliament, I shall satisfy myself with vindicating him from the Reproach of arbitrary & tyrannical Government with which he has often been charged. This, I feel, is not difficult to be done, for with one argument I am certain of satisfying every sensible & well disposed person whose opinions have been properly guided by a good Education — & this argument is that he was a Stuart.

Austen maintains the genre, tone, point of view, etc., but she goes further: she takes the parody to its satisfying conclusion by throwing aside the cloak of a historian’s supposed neutrality, directly stating her skewed intentions, and closing with an unsupported, fallacious argument.

In Conclusion

Typically, the Reader-Writer contract should be established within the first 10-20% of a story. We need buy-in and commitment from our readers.

If you went to the movie theater to watch a romantic comedy and half-way through it transformed into a zombie film, you would probably walk out, unless there had been clues planted at the beginning of the film that a zombie film was coming.

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/68-Square.png

1080

1080

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Katherine-Cowley-Logo-2-1030x589.png

Katherine Cowley2023-09-29 08:47:492023-09-29 08:47:51#68: Establishing Relationships and Character Connections in Fiction

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/68-Square.png

1080

1080

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Katherine-Cowley-Logo-2-1030x589.png

Katherine Cowley2023-09-29 08:47:492023-09-29 08:47:51#68: Establishing Relationships and Character Connections in Fiction https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/68-Square.png

1080

1080

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Katherine-Cowley-Logo-2-1030x589.png

Katherine Cowley2023-09-29 08:47:492023-09-29 08:47:51#68: Establishing Relationships and Character Connections in Fiction

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/68-Square.png

1080

1080

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Katherine-Cowley-Logo-2-1030x589.png

Katherine Cowley2023-09-29 08:47:492023-09-29 08:47:51#68: Establishing Relationships and Character Connections in Fiction