The Exposition

The exposition is the story world in stasis, or as it existed before the inciting incident. For some books, this takes several chapters, for others, a few sentences, and for other stories, we start with the inciting incident and the exposition is delivered through little pieces of interspersed backstory.

In Pride and Prejudice, not much time is spent on exposition at all—news of the inciting incident is delivered on the very first page. Yet the backstory is made clear nonetheless: we understand who these characters are, we quickly grasp the nature of Mr. and Mrs. Bennet’s marriage, learn of the entailment, and understand Mrs. Bennet’s goal: to marry off her daughters so they don’t die in poverty.

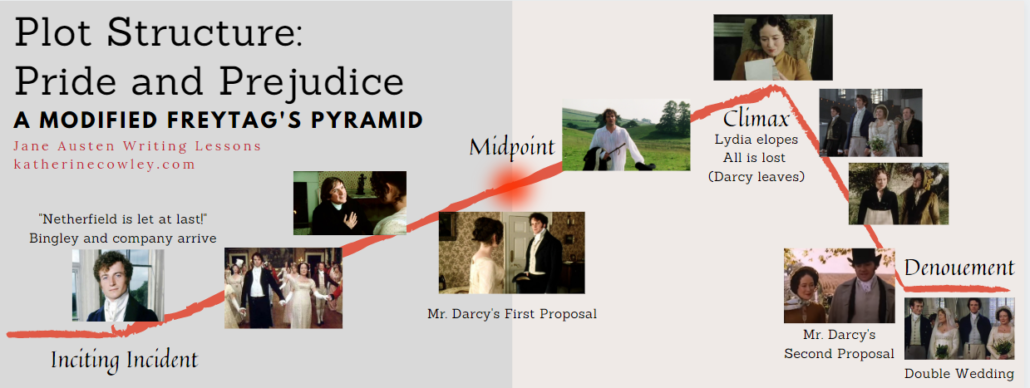

The Inciting Incident

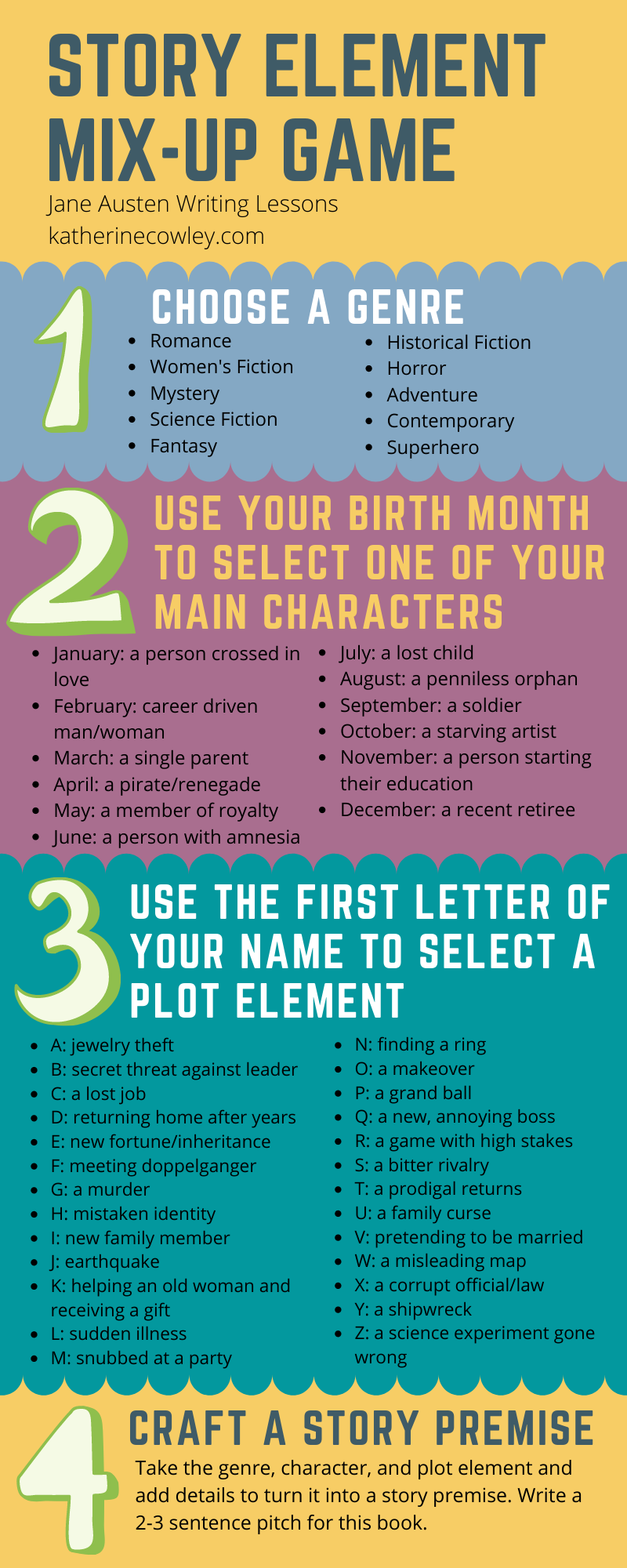

I wrote extensively about inciting incidents in lesson #3, but to recap, an inciting incident is what sets the plot in motion, changing things for the character and starting them on both their internal and external journey.

In Pride and Prejudice, the inciting incident is Mr. Bingley’s arrival. Mrs. Bennet sets her sights on him marrying her eldest daughter, Jane, which becomes one of the major threads of the novel. Mr. Bingley also brings with him his sisters and his good friend Mr. Darcy. Mr. Darcy quickly becomes antagonistic to our protagonist, Elizabeth, and it is these two characters, their pride and their prejudice, and of course, their romance, that creates the main journey of the novel.

Rising Action Part 1

After the inciting incident comes the rising action of the novel. To use Aristotle’s term, this is the “complication.” This is the middle, with all the interesting scenes and incidents and relationships that help and hinder the characters.

In the first half of this rising action, we get some of the most memorable scenes of Pride and Prejudice: two balls, the introduction of Mr. George Wickham, Mr. Collins and his terrible proposal, and Elizabeth’s trip to Rosings. Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy’s relationship changes and develops, circumstances change for many of the other characters, and the themes of the novel are explored and developed.

The Midpoint

Freytag doesn’t talk about the midpoint in his model, but many of the other structures do, because it’s a very powerful turning point that is used in a majority of stories.

The midpoint is an event in which the core aspects of the character’s journey are brought under a lens. The character typically experiences either a major victory, or a major defeat. This moment will provide the tools the main character needs to make it through the climax and falling action—if she chooses to use them.

The midpoint in Pride and Prejudice is Mr. Darcy’s first proposal to Elizabeth. Both Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth display their pride and prejudice in full force. Mr. Darcy tells Elizabeth all the many reasons he has resisted proposing to her (her family, their lack of connections, and their behavior). Elizabeth refuses him. She verbally attacks him for his pride, and she accuses him of splitting up Mr. Bingley and Jane and of ruining Mr. Wickham’s life forever (a falsehood, which shows the pitfalls of Elizabeth’s prejudice).

This moment marks a major shift for the characters, a moment where they begin to change both internally and externally. (Later, Mr. Darcy explains, “I have been a selfish being all my life, in practice, though not in principle. As a child I was taught what was right, but I was not taught to correct my temper. I was given good principles, but left to follow them in pride and conceit.”) After Elizabeth’s refusal, Mr. Darcy begins to treat others with more kindness; Elizabeth begins to question her preconceived notions and opens herself up to forgiveness and new perspectives.

There are several Pride and Prejudice adaptations that structurally move Darcy’s first proposal to the climax location of the story, which often leads to substantive plot and character changes, because then everything after that is falling action. (An example of this is Kate Hamill’s play adaptation of Pride and Prejudice.) However, in the original text, Mr. Darcy’s first proposal happens almost exactly at the midpoint of the novel, and many film adaptations follow suit (for instance, in the 1995 BBC adaptation, the proposal happens at the very end of the third episode, with three episodes remaining for the rest of the rising action, the falling action, and the denouement).

Rising Action Part 2

After the midpoint, we have more rising action, but as Blake Snyder explains in the screenwriting book Save the Cat, it’s not just fun and games anymore. The stakes are higher and more personal for the characters.

Darcy writes a letter explaining his story to Elizabeth, and Elizabeth reads it and realizes how very wrong she has been. The novel contains several chapters of reflection and soul-searching on her part. Elizabeth returns to her home and makes the decision not to expose Wickham’s true character. She then takes a trip to Derbyshire with her aunt and uncle, and while there they visit Darcy’s home, Pemberley, thinking he is not home. Darcy’s servants testify of his true character, and then Darcy appears. He has changed—he goes out of his way to be friendly and polite to Elizabeth’s aunt and uncle.

The Climax

The climax is the point where all the themes and conflicts of the novel come to a crisis, and where it seems impossible for the characters to get what they want.

In Pride and Prejudice, the climax is when Elizabeth receives Jane’s letter and finds out that her youngest sister, Lydia, has ran off with Mr. Wickham. This truly is a crisis: the whole family will likely be ruined when word of this gets out, and Elizabeth will have no chance of a good marriage. Further, she believes that now Mr. Darcy must despise her—everything he disliked about her family before pales in comparison to this. Mr. Darcy immediately leaves, and Elizabeth is certain that she will never see him again.

Falling Action

The falling action, or what Aristotle called the unravelling, is when all the final problems are addressed. Now the characters are really put to the test: will they be able to use what they learned from the midpoint to conquer the crisis?

In some genres, this would be the big final battle; a Jane Austen story may not have an actual battle, but the stakes are just as high, and the circumstances challenge the characters to their limits.

In Pride and Prejudice, Darcy proves himself in the falling action by finding Lydia and Wickham, forcing them to marry, and providing them with financial support—all without taking any credit for it.

Elizabeth goes home and provides endless support for her family members. Then, when Lady Catherine de Bourgh visits in an attempt to intimidate Elizabeth into submission (and into promising never to enter into an engagement with Mr. Darcy), Elizabeth uses her pride in a useful way, to defend herself and stick to her principles. This event ultimately leads Darcy to realize that he still has a chance with Elizabeth.

The last test of their characters is if Elizabeth and Darcy can let go of their pride one last time and be fully reconciled to each other.

Resolution and Denouement

The resolution of the plot is the final event or moment that resolves or solves the final, major questions that have been raised. The denouement ties up loose ends, and the main characters end up better off than they were at the start of the novel.

Elizabeth and Darcy are able to converse earnestly and deeply, and Darcy proposes. This proposal, and Elizabeth’s acceptance, contrasts strongly with the original proposal: they have let go of their prejudices and made themselves vulnerable to each other.

The denouement consists of two sets of marriages: Jane to Bingley, and Elizabeth to Darcy. Other minor things are wrapped up: Kitty, we find, becomes “less irritable, less ignorant, and less insipid.” Lady Catherine is “indignant,” but ultimately “[condescends] to wait on them at Pemberley.”

On Tragedy

In the Aristotelian tradition, there are only two genres: tragedy and comedy. Anything that is not tragedy is a comedy using this model. Sarah Emsley has made the argument that Austen’s Mansfield Park is a tragedy rather than a comedy, something that will be discussed in more detail in a future lesson.

In a tragedy, the climax is often a high point rather than a crisis. The main character does not learn the lessons they needed to learn: their character does not shift and grow, which leads, in the falling action, to their literal fall. In the denouement, we see their ruin: the main character is worse off than they were at the beginning of the story.

In Sum

The rising action, the sense of building, engages the reader. We become more and more invested in the story, and as a result, the falling action leaves us feeling satisfied. The characters’ internal journeys and growth are interwoven with the main points of the plot structure.

As a disclaimer, many short stories and some novels do not use this structure. Yet even though this plot structure is not universally used, it’s a useful construct that helps us understand what readers expect from stories and an approach that typically is effective at creating an external journey for the main character.

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/68-Square.png

1080

1080

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Katherine-Cowley-Logo-2-1030x589.png

Katherine Cowley2023-09-29 08:47:492023-09-29 08:47:51#68: Establishing Relationships and Character Connections in Fiction

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/68-Square.png

1080

1080

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Katherine-Cowley-Logo-2-1030x589.png

Katherine Cowley2023-09-29 08:47:492023-09-29 08:47:51#68: Establishing Relationships and Character Connections in Fiction https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/68-Square.png

1080

1080

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Katherine-Cowley-Logo-2-1030x589.png

Katherine Cowley2023-09-29 08:47:492023-09-29 08:47:51#68: Establishing Relationships and Character Connections in Fiction

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/68-Square.png

1080

1080

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Katherine-Cowley-Logo-2-1030x589.png

Katherine Cowley2023-09-29 08:47:492023-09-29 08:47:51#68: Establishing Relationships and Character Connections in Fiction